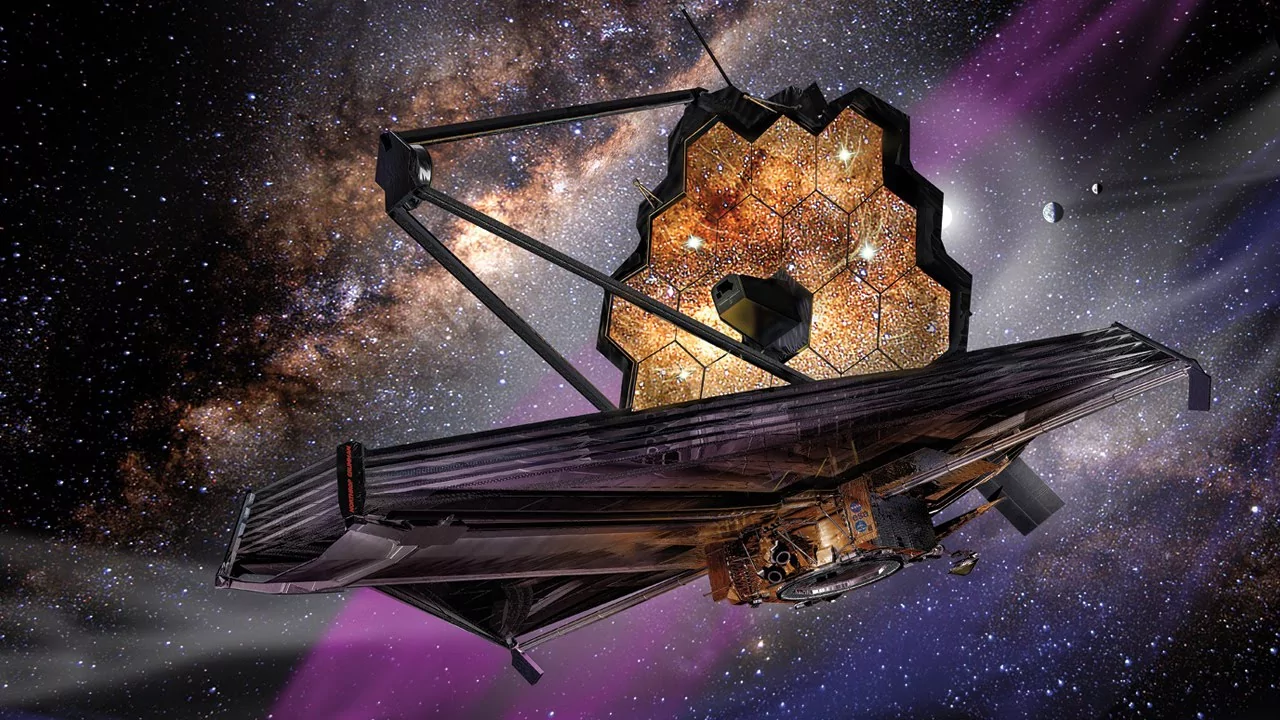

Cosmic monsters live in dense star clusters that were born just a few hundred million years after the birth of the universe, according to new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). These monsters are supermassive stars. JWST It has been observed in globular clusters that were born about 13.4 billion years ago.

Globular clusters are found in almost every galaxy; ours, Milky Wayat least 180 of them. Globular clusters are not only the most massive and oldest groups of stars, they often contain up to one million stars that were born together 440 million years after the Big Bang, However these stars may exhibit anomalies not found in other star collections.

For example, stars globular cluster, Although they arise from the same collapsing cloud of cold gas and dust at the same time, they typically show a high level of compositional variation. The ratio of oxygen, nitrogen, sodium, and aluminum in globular clusters varies from one star to the next. Explaining these so-called “number anomalies” has become a serious problem for astronomers.

One possible explanation for this mystery, proposed in 2018, is that supermassive stars “contaminated” the original gas cloud during the formation of globular clusters. This leads to the fact that young people: stars unevenly enriched with chemical elements during formation.

Now, a research team has announced that JWST has detected chemical signatures that suggest monstrous stars are indeed lurking in star clusters, thus providing the first observational evidence for this enrichment theory.

“Today, thanks to data collected by JWST, we believe we have found the first clue to the existence of these unusual stars,” he said. lead author of the study is Corinne Charbonnel, professor of astronomy at the University of Geneva in Switzerland (opens in a new tab).

These supermassive stars They are 5,000 to 10,000 times heavier than the Sun and have temperatures of 135 million degrees Fahrenheit (75 million degrees Celsius) at their cores and 27 million degrees F (15 million degrees Celsius) at the heart of the sun. But despite their formidable size and freezing temperatures, these star animals aren’t always easy to find. This is because fusion fuels burn quickly and are therefore short-lived.

“Global clusters are between 10 and 13 billion years old, while superstars have a maximum lifetime of two million years,” team member Marc Giles of the University of Barcelona said in the same statement. “Therefore, they disappeared very early from the currently observable clusters. Only indirect traces remain.”

To detect signs of these supermassive stars, the research team resorted to JWST’s infrared vision to capture globular clusters in their early stages of formation. A powerful space telescope spotted the light emitted by one of the most distant and oldest planets. galaxies, found so far, GN-z11. The galaxy is about 13.3 billion light-years away, and JWST sees it as it was when it was only a few tens of million years old, making it a good choice for hunting young globular clusters.

Since chemical elements absorb and emit light at certain frequencies, the light spectrum from cosmic sources contains “fingerprints” that indicate the composition of celestial bodies. The astronomers took the light from GN-z11 seen by JWST and in the process found two valuable pieces of information and smashed it.

“It has been found that he [GN-z11] “It contains very high percentages of nitrogen and very high density of stars,” said Daniel Scherer, professor of astronomy at the University of Geneva.