Researchers at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) have created a new tool that could help uncover the origins of electronic states in technical materials and pave the way for their use in future applications of quantum technology. Associate Professor Shuolong Yang and his team developed this innovative tool to improve the understanding of magnetic topological insulators, materials with unique surface properties that could play a critical role in the development of quantum information science technologies.

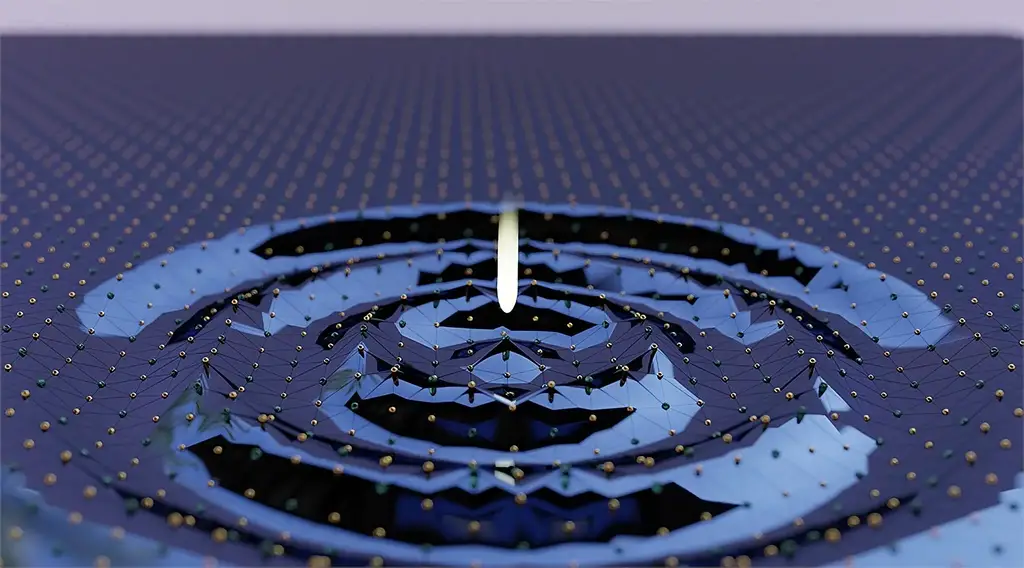

Using a technique called layer-encoded frequency-domain photoemission, the researchers send two laser pulses into the layered material. The resulting vibrations, combined with energy measurements, allow the researchers to create a “film” of how electrons move in each layer.

“In our daily life, when we want to better understand a material — its composition or whether it’s empty — we click on it,” Yang said. “This is a similar approach at the microscopic level. Our new technique allows us to ‘knock and listen’ to layered materials, and it allowed us to show that a particular magnetic topological insulator works differently than the theory predicts.” The results were published in the journal Nature Physics.

Understanding layered materials is important because many materials scientists now design and create materials at the atomic level through the layering process by combining two or more materials to form a new material. Creating these materials from scratch allows them to create materials with new properties for future technologies.

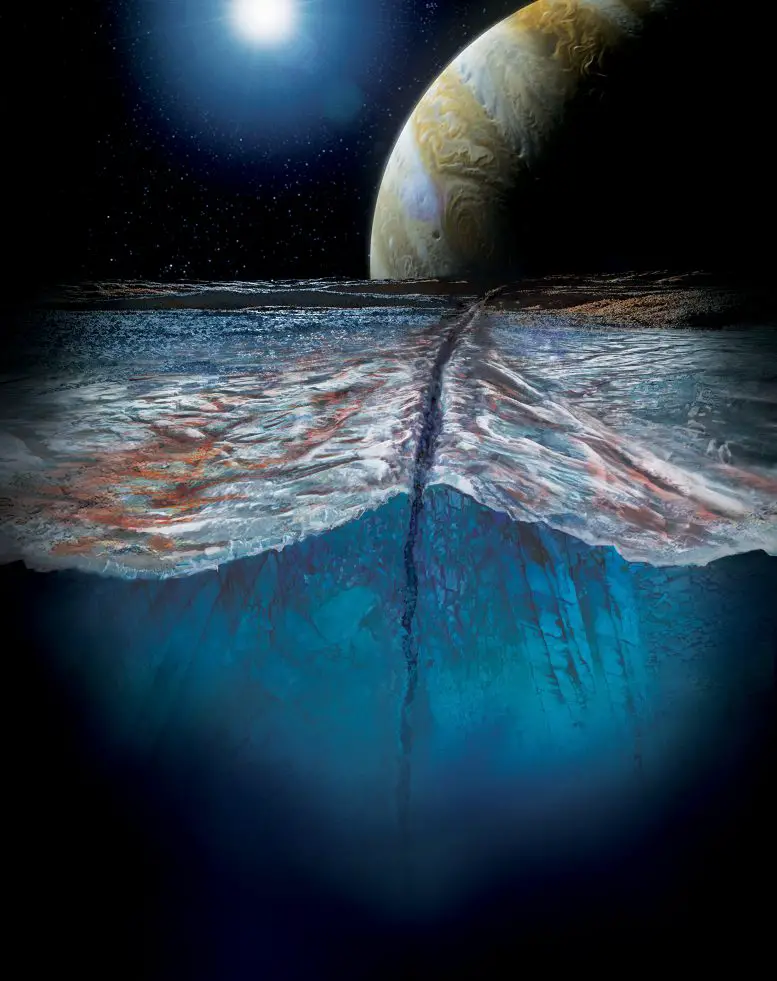

Scientists developed a material with exotic quantum properties when they combined a magnetic material with a non-magnetic material to create a double-layer magnetic topological insulator (MnBi2Te4)(Bi2Te3). Electrons move along the circumference of the surface while maintaining their energy and quantum properties. This supercurrent could potentially be used in future quantum computers to transmit information stored in qubits.

Because these layers are so thin (on the order of a few nanometers), traditional material characterization tools such as spectroscopy cannot separate the layers from each other. While electrons should ideally travel around the surface of a magnetic material, previous experiments by other groups have shown that it is possible for them to orbit a nonmagnetic material instead.

The result contradicts the theoretical predictions

The new device first sends a femtosecond (or quadrillionth of a second) infrared pulse to understand what’s going on in the two different layers. This short pulse causes the layers to vibrate differently depending on their composition. The researchers then send out a second pulse of ultraviolet laser, which can measure the energy and momentum of the electrons in the material. Together, these two measurements can record the movement of electrons over time.

“It’s actually a femtosecond time scale movie,” Yang said. “And this allows us to identify which electrons are from which layer.”

When they applied this technique to the material (MnBi2Te4)(Bi2Te3), they found that, contrary to the theoretical predictions, there was no special electronic state in the magnetic layer. However, since this supercurrent would have significantly improved the material’s quantum properties if it had traveled through the magnetic layer, Young and his team encouraged the research community as a whole to return to the drawing board to redesign the material.

Yang says the technique could also be used to better understand other specialized materials, such as topological superconductors and so-called twisttronics, which are layered materials arranged at certain angles to create different electronic behaviors.

“When designing new materials for future applications, it’s important to have a link between synthesis and characterization,” he said. “This will guide the next iteration of synthesis and help us fill the technology gap.”