NASA wants to detect phytoplankton species from space

- June 23, 2023

- 0

They are small but powerful. From producing the oxygen we breathe to absorbing the carbon we emit to feeding the fish we eat, tiny phytoplankton are an essential

They are small but powerful. From producing the oxygen we breathe to absorbing the carbon we emit to feeding the fish we eat, tiny phytoplankton are an essential

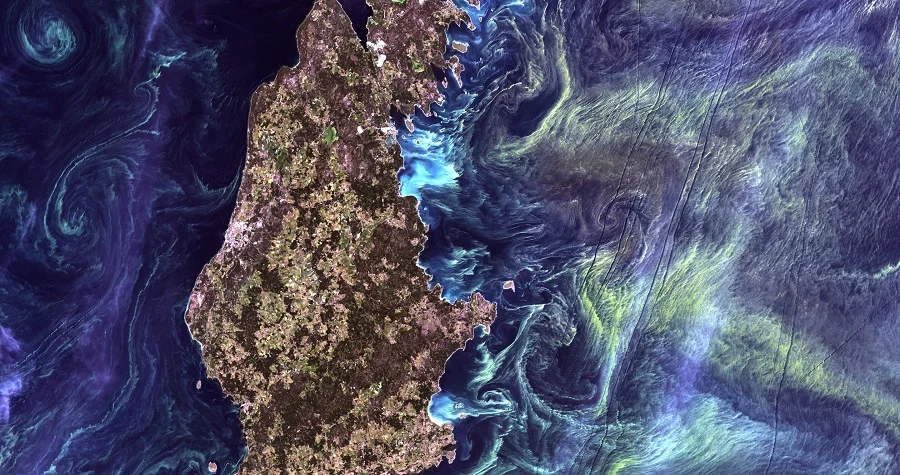

They are small but powerful. From producing the oxygen we breathe to absorbing the carbon we emit to feeding the fish we eat, tiny phytoplankton are an essential part of ocean ecosystems and essential to life as we know it on Earth. To provide new insight into these remarkable aquatic organisms, NASA is launching a satellite in early 2024.

Instruments on the PACE (short for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, and ocean Ecosystem) satellite will observe the ocean and collect data on the colors of light reflected from the ocean, telling us where different phytoplankton species evolved. The Ocean Color Instrument on PACE will be the first science satellite to observe over 100 different wavelengths and do so on a global scale every day. This “hyperspectral” tool will allow for the first time the identification of phytoplankton by species from space.

Phytoplankton are tiny organisms that float on the surface of the ocean and other bodies of water. Like land plants, phytoplankton use photosynthesis to absorb sunlight and carbon dioxide and produce oxygen and carbohydrates, which are carbon-filled sugars. These sugars make phytoplankton the center of the ocean’s food web: they feed large animals, from zooplankton to mollusks and fins, and are then eaten by larger fish and marine mammals. The formation of sugar by the action of sunlight is called primary production.

Although phytoplankton makes up less than 1% of the total photosynthetic biomass on Earth, it provides about 45% of the world’s primary production. Without phytoplankton, most oceanic food webs would collapse, destroying both marine life and people who rely on fish for food.

Tiny organisms provide more than nutrients. Thanks to photosynthesis, phytoplankton create oxygen, which is released into the ocean and atmosphere. In fact, since phytoplankton began photosynthesizing more than 3 billion years ago—more than two billion years before land plants and trees emerged—phytoplankton has been producing about 50% of all oxygen produced on Earth.

Photosynthesis also gives them an important role in the global carbon cycle as they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. What phytoplankton does with this carbon depends on the species.

“Like plants on land, phytoplankton are very diverse,” said Ivona Cetinich, a biological oceanographer at NASA’s Ocean Ecology Laboratory at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. She said that each of these various species has different characteristics that allow them to do different jobs in Earth’s carbon systems.

Phytoplankton such as Emiliana huxleyi store carbon in their shell-like outer shells. When shells die, they sink and absorb carbon from the depths of the ocean. Other phytoplankton species occupy a special niche for picky eaters, such as oysters, which eat only phytoplankton of a certain size. Other phytoplankton species can capture carbon through photosynthesis, where the organisms remain on the ocean surface until they decompose and return the carbon to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

“My hope is that PACE, after giving us a look at the diversity of ocean phytoplankton, can tell us much more about the global carbon flux in the oceans now and in the future,” Cetinich said. Said.

Even in colder waters at higher latitudes, phytoplankton is critical to ocean life. In polar regions, phytoplankton blooms—when organisms grow and multiply in large numbers visible from space—can follow a cycle of sea ice melt.

As the sea ice layer recedes, sunlight can reach the surface of the ocean and the phytoplankton floating on it, enabling them to photosynthesize and thrive after being under cover for a long time. This produces fuel for other species. From oysters and krill to walrus and whales, arctic species rely on these timely blooms for their food source.

“Changing bloom times affect the entire ecosystem,” said Amy Neely, a biological oceanographer at NASA Goddard.

As the timing and extent of sea ice retreat changes under a warming climate, PACE will be able to track changes in flowering timing and provide insight into broader ecosystem impacts.

Not all phytoplankton are beneficial to ecosystems. Some species can produce toxins that are dangerous to humans and other marine species. These harmful algal blooms can disrupt ecosystems as well as disrupt the daily lives of people near coasts, lakes and rivers. For example, cyanobacterial eruptions can contaminate drinking and recreational waters with the toxins they produce.

The scientists used some satellite data to track and monitor this bloom and the conditions that caused it. PACE should facilitate the deciphering of these species and conditions and enable people to develop ways to mitigate the effects and prevent future blooms.

“Not all phytoplankton cause harmful algal blooms, so if we can use satellite data to better separate harmful blooms from harmless ones, it would be beneficial for water managers and scientists trying to understand phytoplankton communities in the area,” Bridget said. Seegers, a NASA Goddard oceanographer.

PACE won’t be the first satellite to see phytoplankton from space. This mission is the successor to missions such as Terra, Aqua, Landsat and SeaWiFS (Wide Field of View of the Sea), which have been collecting phytoplankton data since the 1990s. Assembled and operated by NASA Goddard engineers, PACE will greatly enhance our ability to discern and monitor phytoplankton every day across the planet.

“We hope that the hyperspectral nature of the Ocean Color Instrument will allow us to better distinguish phytoplankton species from each other and from non-phytoplankton particles,” said Neely. “The research opportunities for me will be endless.” Source

Source: Port Altele

As an experienced journalist and author, Mary has been reporting on the latest news and trends for over 5 years. With a passion for uncovering the stories behind the headlines, Mary has earned a reputation as a trusted voice in the world of journalism. Her writing style is insightful, engaging and thought-provoking, as she takes a deep dive into the most pressing issues of our time.