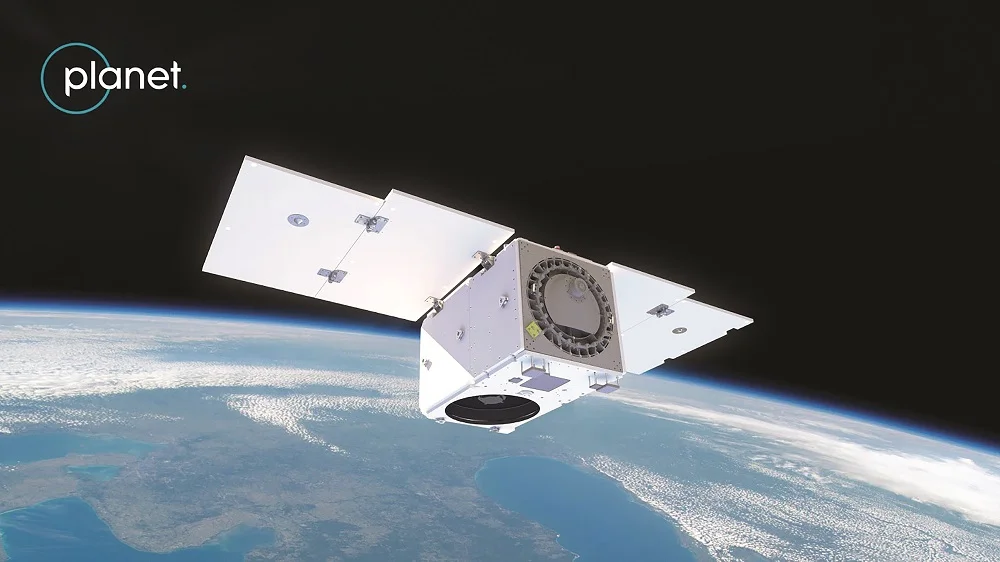

The Federal Communications Commission requires satellite array operators to work with astronomers to minimize the impact of their satellites on ground-based astronomy. On August 31, the FCC allowed Iceye and Planet to renew their licenses to add new satellites. Iceye, which operates a fleet of synthetic aperture radar imaging satellites, added eight satellites to its license, while Planet added seven of its Pelican high-resolution imaging satellites to its fleet.

Both licenses now include provisions requiring companies to coordinate with the National Science Foundation (NSF) “to reach a mutually acceptable agreement to reduce the impact of their satellites on ground-based optical astronomy.” Companies are required to report annually to the FCC whether they have a coordination agreement with NSF and what steps they have taken to reduce their satellites’ impacts on astronomy, unless NSF concludes that they have no concerns about those spacecraft.

In January, NSF announced a similar coordination agreement with SpaceX to help reduce the astronomical impact of the Starlink constellation, including the larger V2 series satellites. Such an agreement was a condition of the FCC’s license for the second-generation Starlink system, but NSF and SpaceX voluntarily drafted the agreement before the FCC granted the license.

While individual Icy Eye constellations or Planets pose no risk to astronomy, given the small number of moons compared to mega-constellations like Starlink, astronomers are concerned that large numbers of such constellations together could interfere with astronomy.

“If we have a lot of small constellations, the total number can be large,” Ashley Wanderley of NSF’s Division of Astronomical Sciences said while discussing the icy eye and planet at the Sept. 19 Astronomy and Astrophysics Advisory Committee meeting. Coordination requirements in FCC licenses.

“The Federal Communications Commission has done a great job taking our concerns into account,” he said, “and for that we are grateful.”

The main part of astronomers’ concern is still connected with large constellations. These concerns emerged four years ago with the launch of the first Starlink satellites, whose brightness caused alarm. Since then, astronomers, along with SpaceX and other companies, have been trying to reduce the brightness of these satellites to minimize, if not completely eliminate, their impact on astronomy.

“We work really well with SpaceX,” Wanderley said, because the company has taken steps to reduce the brightness of Starlink satellites so they don’t exceed magnitude 7.

NSF is also working on coordination agreements with OneWeb and Amazon for its groups. According to him, the OneWeb deal has been completed and is planned to be made public in the near future. NSF is in the “final stages of discussions” with Amazon on a coordination agreement for Kuiper that should be announced this fall.

Amazon plans to test obfuscation with its first two prototype satellites, which are scheduled to launch with United Launch Alliance’s Atlas 5 in the first week of October. One of the satellites will be equipped with an unspecified method to reduce its brightness, while the other will not use this feature. Testing how effective these measures are before launching additional satellites.

“Major satellite companies are working hard on mitigation,” Wanderlee said, adding that this effort will extend to future systems such as the planned second-generation OneWeb array. Source