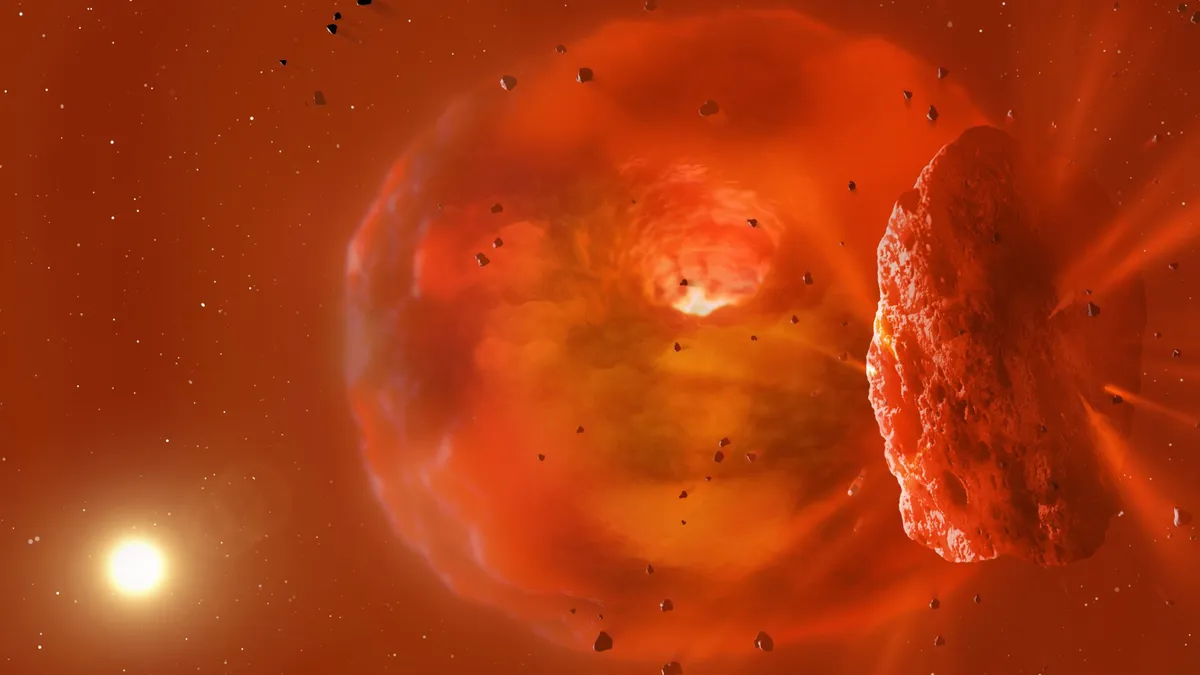

Astronomers have detected debris left over from the massive collision of two giant icy planets around a distant sun-like star. Using a NASA spacecraft monitoring the sky for asteroids, scientists also discovered a bright afterglow created by planetary breakup and the resulting dust cloud that crossed the surface of the system’s host star, darkening it significantly.

A curious astronomer reported the collision to the team after noticing that the star, called ASASSN-21qj and located about 3,600 light-years from Earth, had a strange emission of light that doubled in intensity in the infrared and disappeared into the visible after three years. . shiny.

“An astronomer noted on social networks that the star became brighter in the infrared range 1,000 days before the optical extinction. That’s when I realized that this was an unusual event,” said Matthew Kenworthy, co-leader of the study and researcher at Leiden University. inside expression. “To be honest, this observation was a complete surprise to me.”

The researchers simulated how such a collision would occur, simulating the initial impact and subsequent scattering of particles from the collision. This indicated that the ASASSN-21qj planets likely merged into a single body after the collision.

The simulations allowed the team to determine how the debris cloud would expand outward from the impact site, causing it to darken in visible light as it would take three years to travel the distance to cover ASASSN-21qj as seen from Earth.

“Our calculations and computer models show that the temperature and size of the glowing material, as well as the duration of the glow, are consistent with a collision between two icy giant exoplanets,” said co-author Simon Locke. Bristol explained.

Determining the temperature of this planetary debris also helped the team deduce what the infrared glow produced by this violent event would look like. Emissions matching this profile were detected by NASA’s Near-Earth Object Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE) spacecraft, which searches for asteroids and comets in our solar system.

Researchers continued to study ASASSN-21qj for two years, monitoring how its brightness changed over time. They published their findings October 11 in the journal Nature. The team found that the collision of two ice giants likely caused the infrared brightness to double three years before ASASSN-21qj began to fade in visible light.