Neanderthals, who disappeared from the archaeological record about 40,000 years ago, have long been considered our closest evolutionary relatives. But since Neanderthal remains were first discovered in the 1800s, scientists have debated whether Neanderthals were their own species or simply a subset of our own species, Homo sapiens, which has since become extinct.

So what does science say? Specifically, genetic evidence suggests that many early hominids did not exist when they were first discovered?

Jeff Schwartz, a physical anthropologist and professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh, told Live Science that the question of whether Neanderthals can be considered the same species as modern humans is complicated by our understanding of what a species is. The most common definition, called the biological species concept, defines a species as a group of individuals that can interbreed in nature and produce viable offspring. But even today a few strange hybrids do not fit this description.

“Horses and donkeys can breed, but the mules they give birth to are sterile, so the two species are considered separate species,” Schwartz said. But other combinations produce viable offspring. These include the liger (a hybrid of a lion and a tiger) and the bifalo (a hybrid of a cow and an American bison).

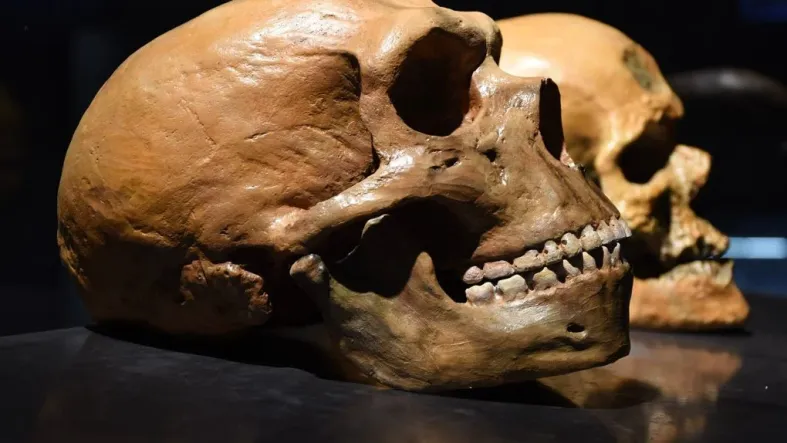

Scientists long didn’t know whether Neanderthals and modern humans interbred, so this description wasn’t very instructive. Instead, early guesses were made based on Neanderthal anatomy, which was very different from Neanderthal anatomy. sapiens Experts can usually separate bones into two groups. Neanderthals, for example, had a longer, lower skull, a bony forehead, and a less prominent jaw. sapiens and their bodies were stockier.

For this reason, Neanderthals were first classified as their own species in 1864. H. neanderthalensis . But since earlier human relatives were discovered erectus in 1891 H. heidelbergensis in 1907 and H. habilis In 1960, their relations with each other became increasingly difficult. Compared to other species, Neanderthals looked much more “human,” Schwartz said. Recent research has shown that both groups had similar hearing and vocal abilities, and conflicting findings suggest that Neanderthals buried their dead and made jewelry and art.

In 1962, a group of anthropologists, geneticists, and behaviorists met in Austria to develop and poll the evolutionary history of human relatives based on species discovered at the time. His articles titled “Classification and Evolution of Man” describe Neanderthals sapiens as a subgenre, Schwartz said, “They taught me that when I was in college.”

It was only in the 1970s and 1980s that Neanderthals were reclassified as their own species based on new analysis, and this remains the most common description seen today.

But the discovery in 2010 shook things up again: An international group of dozens of researchers published the first draft of the Neanderthal genome, based on three individuals, and compared it to the genome of modern humans. The authors found clues to Neanderthal traits in the human genome; This suggests that Neanderthals mixed with modern human ancestors at least 120,000 years ago. Dozens of studies have since confirmed this and found that interbreeding occurred at different times.

“The conclusion is clear: Neanderthals and humans interbred,” Jaume Bertrandpetit, an evolutionary biologist at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, told LiveScience. sapiens it also interbred with another early hominid group, the Denisovans. Therefore, he said, it is possible that all three represent different versions of the same species.

Bertrandpety cited modern humans as an example. People around the world have distinct differences in their bodies, skin, hair and eye colors, but genetically we are quite similar. The level of genetic diversity between any two individuals is only around 0.1%; This means that only one in every 1000 base pairs will be different. By comparison, a paper published in 2010 showed that the Neanderthal genome was 99.7% identical to the genomes of five modern humans.

“Big differences in morphology don’t mean you have to have big differences in genetics; It just means you need some differences in certain genes,” Bertrandpetit said. “So the idea that these are different species doesn’t make any sense to me as a geneticist.”

Schwartz doesn’t think genetic evidence will necessarily resolve the debate, but he doesn’t doubt the rigor of work done by other groups. Going forward, he advocates an interdisciplinary approach that does not position genetics as the final word. “We need a holistic approach and we cannot continue to pit one discipline against another,” he said. “We need to come together and solve this problem.”