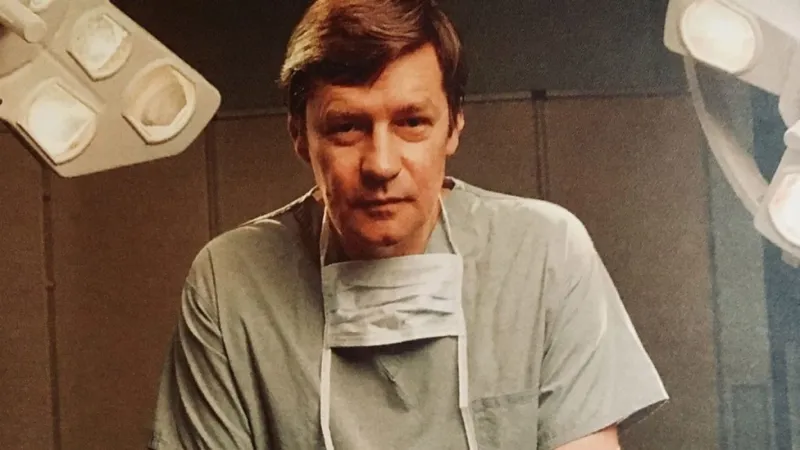

Surgeon who saved thousands of lives due to brain damage…

- June 5, 2022

- 0

Stephen Westaby has published his memoirs in two books: Fragile Lives: The Life and Death Stories of a Cardiac Surgeon on the operating table (2017) and The Razor’s

Stephen Westaby has published his memoirs in two books: Fragile Lives: The Life and Death Stories of a Cardiac Surgeon on the operating table (2017) and The Razor’s

Stephen Westaby has operated on more than 12,000 hearts and estimates he has saved 97% of his patients.

This is impressive in itself.

But Westaby, now 73, is also an innovative pioneer, internationally recognized for helping develop and improve the use of heart pumps, artificial hearts, and circulatory support technology to move blood throughout the body.

However, he says his professional career would have been very different had it not been for the blow he received at the age of 18.

Although he always saw his profession clearly. Westaby knew what she wanted to do with her life when she fell under the spell of a television show at age 7.

After seeing a heart-lung machine in action in the then-new BBC medical series Your life is in their hands (Your life is in his hands), he decided to become a heart surgeon.

The illness and painful death of his beloved grandfather cemented his decision.

“One day, while walking the dog, he grabbed his chest and fell to his knees. About half an hour later he got up and went home,” he said. BBC View.

“We didn’t know what he had been through was a heart attack. Then I saw that he had another one and then he sank into a swamp. severe heart failure, carries a miserable existence.

“Finally one day I came home from school and saw the doctor’s car in front of my grandfather’s house. I walked in very quietly and watched my grandfather die out of the blue before I could breathe.”

It was the same grandfather who realized that he had a grandson. he had an invaluable talent for a surgeon.

“He understood that I was versatile. He taught me how to paint and saw that I could draw with both hands.

Although predominantly right-handed, he could handle a pencil, brush (and ultimately surgical instruments) with both hands.

With that dexterity and an unusually precise spatial awareness that allowed him to draw well, he had two points in his favor for being what he wanted.

But there was one against it, and a very big one.

“Surgeons need the right temperament,” Westaby said in an article in the journal. daily mail.

“You must be able to explain the death to grieving relatives. You must have the courage to comfort your boss when he is tired, the courage to take charge of the post-operative care of young babies or face the disasters in the trauma room.

«I was a shy, modest, humble child. He I know frightened from him own shadow«.

So much so that when he was presented with the opportunity to study at Cambridge, one of the best universities in the world, he turned it down, thinking that he would feel alienated.

Instead he chose Charing Cross Medical School in London and thought he could go unnoticed there any longer. It was. At first, college life was uneventful, for better or worse.

What he did was learning to play rugby that changed his life.

In 1968 we went on tour playing rugby. “We were up against a team from Cornwall with some very tough players on a gray winter day and I got a blow to the head and broke the front of my skull.”

“I was seeing the stars in the dressing room and, Instead of taking me to the hospital,anyonemedical students me bar. After drinking a few pints of beer and losing consciousness, I woke up very sick the next day.”

Now they have sent him to the hospital. Not only did he miss the rugby tour, it could also have been the end of his medical career.

But the incident, oddly enough, had the opposite effect.

“The first night at the hospital I, that withdrawn and shy boy, flirted with the nurse who took care of me.”

When they tried to treat him, he reacted aggressively like he had never done before.

Something had changed.

X-rays revealed a small crack in the frontal bone of the skull.

“The head injury affected the part of my brain responsible for critical reasoning and risk aversion. This explained my new lack of inhibition, irritability and occasional aggression.

“Psychologists’ tests showed that I score high on something called the ‘psychopath personality inventory,’ and the psychologist told me, ‘Don’t worry, most successful people are psychopaths. Especially surgeons.”

“It was expected to return to normal when the swelling subsided, but luckily for me it didn’t,” he said.

What the head injury did was take away his fear and shyness..

“Suddenly I became the social secretary of the medical school that organized the hospital dances and soon became the captain of rugby and cricket.”

“I seemed unaffected by stress and a constant thrill-seeking adrenaline junkie, I made a habit of taking risks. In short, I came out of the head injury experience unhindered and ruthlessly competitive.”

Westaby now had “all the skills for a successful surgeon”: coordination, dexterity and audacity.

“The last thing you want is to be a scared surgeon.”

Westaby lived for the next forty years In that tense zone between life and death, marked by the sound of your heartbeat.

Among other things, he specialized in complex pediatric surgery or infant operations and developed a method of cardiac surgery that does not require intensive care.

But there was one area that stood out: the potential of artificial hearts.

“People with heart failure can be helped, but heart transplants are very rare. You need someone to die to give you that organ.”

«I always thought there had to be a better way, a mechanical solution«.

But the artificial hearts were too big, bulky and useless.

“One day in 1993 I met an engineer named Robert Jarvik who was working on artificial hearts.”

It was the beginning of a partnership that would revolutionize cardiac surgery.

Jarvik had invented a pump that helped circulate blood throughout the body, but he didn’t know how to keep it going. Here is Dr. Westaby stepped in. Together they created the Jarvik 2000, a miniature battery-powered turbine.

“The first person to own the Jarvik 2000 was a 59-year-old man named Peter Houghton.”

At the Oxford Research Laboratory, Westaby was told he could only fit the device into a patient whose life expectancy was only a few weeks.

“When she was wheeled into my office, her ankles were swollen, her lips were blue, her belly was swollen. She reminded me of my grandfather just before he died, and so I was desperate to help him.”

Peter would live another 8 years, which is much longer than anyone who had an artificial heart at the time..

Meanwhile, Westaby was gaining fame not only in the medical community. In 2004 he received a phone call with echoes from the past.

It was some television producer who wanted to make a program of his name. your life is in their hands With me”.

“I automatically told them I would be happy to talk to them because that’s the show I watched when I was 7 years old.”

Source: El Nacional

Alice Smith is a seasoned journalist and writer for Div Bracket. She has a keen sense of what’s important and is always on top of the latest trends. Alice provides in-depth coverage of the most talked-about news stories, delivering insightful and thought-provoking articles that keep her readers informed and engaged.