The therapy has allowed people to see stars or snowflakes for the first time and to better navigate their daily lives. Results from ongoing trials show the drug is safe and effective, paving the way for more widespread use once it receives FDA approval.

Transformational vision restoration

After treatment, one patient saw her first star. Another saw snowflakes for the first time. Other patients were soon able to walk around outside the house or read their children’s candy labels.

The reason for these seemingly miraculous developments? A gene therapy developed by scientists at the University of Florida that, in a small study, restored useful vision to most patients with a rare inherited form of blindness known as Leber congenital amaurosis type I, or LCA1.

Breakthrough in gene therapy

Those who received the highest doses of gene therapy had a 10,000-fold increase in light sensitivity, were able to read more lines on an eye chart and had an increased ability to navigate a standard maze. For many patients, it was like finally turning on a dim light after years of trying to navigate their homes in pitch darkness, the researchers said.

The trial also examined the safety profile of the treatment. Side effects were mostly limited to minor surgical complications. The gene therapy itself caused mild inflammation, which was treated with steroids.

Achievements and future prospects

“This is the first time that anyone with LCA1 has been treated, and we showed a very clean safety profile and we also showed efficacy. These results pave the way for the treatment to advance to phase 3 clinical trials and eventually commercialization,” said Shannon Boye, Ph.D., co-author of the study and co-founder of Atsena and head of UF’s Department of Cellular and Molecular Therapies at UF. Therapeutics, a division of UF that developed the gene therapy and funded the research.

“Atsena is pleased to advance the groundbreaking work that Shannon and Sanford Boye developed in their lab years ago and is excited to have 12-month data from our ongoing clinical trial published in a prestigious medical journal,” said Kenji Fujita, MD, Chief Medical Officer of Atsena Therapeutics and co-author of the study. “We look forward to further results from this program as we continue to make progress on what has the potential to be a breakthrough in the treatment of blindness in children and adults with LCA1.”

Shannon Boye, professor of pediatrics at UF, and Sanford Boye, assistant research professor of pediatrics, and their collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania and Oregon Health & Science University, published the results of the clinical trial Sept. 5 in the journal Cell. Lancet .

A pioneering treatment for LCA1

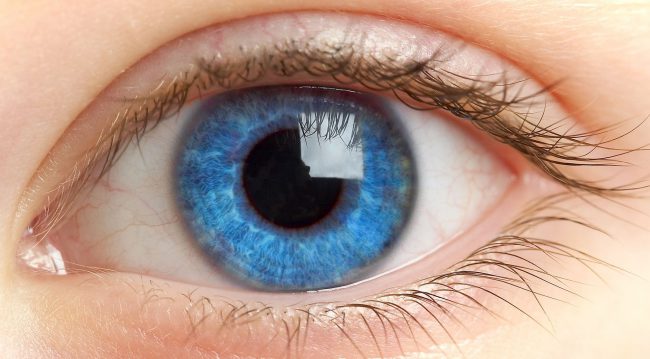

LCA1 is rare. Only about 3,000 people in both Europe and the US have the condition. This is because there are two faulty copies of the gene. GUCY2DIt is necessary for the light-sensitive cells in the eye to function properly. People with this condition often have severe vision impairments, making it difficult or impossible for them to drive, read, or visually navigate the world.

Shannon Boye has been developing gene therapy targeting LCA1 for more than 20 years, since joining the University’s graduate program in 2001. Shannon Boye’s lab, in collaboration with her husband Sanford Boye, developed a virus-based delivery system needed to deliver functioning copies of a gene GUCY2D in right eye cells. Boyes founded Atsena Therapeutics in 2019 to bring LCA1 treatments and other gene therapies to market.

“Most pharmaceutical companies are not interested in treating these rare diseases because they don’t have a strong revenue stream,” said Sanford Boye, “but we believe these patients deserve attention because we have effective treatments that really make a big difference in their quality of life.”

The study recruited 15 people for treatment at the University of Pennsylvania or Oregon Health & Science University. Subjects received one of three different treatment doses to determine the safest and most effective dose for future trials. All patients received treatment, which included surgical injections into the retina in one eye.

The researchers followed the patients for a year to check vision in the treated eye compared to the untreated eye. Subjects who received the higher dose experienced greater improvements in vision.

The researchers expect the gene therapy to last indefinitely, requiring only one procedure for each eye. So far, they’ve seen visual improvements last at least five years.

Broad access to the treatment will require FDA approval following a phase 3 clinical trial testing the treatment in a broader patient population. To learn more about this research, see Seeing 10,000 Times Better: Gene Therapy Produces Life-Changing Results .