No, the new Langya virus did not cause an epidemic in China and…

- August 28, 2022

- 0

Some shrew species transmit the Langya virus. Photo: Pixabay A few weeks ago, the discovery of a new virus in China made headlines in many international media: the

Some shrew species transmit the Langya virus. Photo: Pixabay A few weeks ago, the discovery of a new virus in China made headlines in many international media: the

A few weeks ago, the discovery of a new virus in China made headlines in many international media: the Langya virus. This news probably wouldn’t have gone unnoticed years ago if it weren’t for the fact that we’re all so sensitive about viruses, pandemics and the Chinese right now.

Indeed, the search and discovery of new viruses is very common, especially since we have new metagenomic tools that allow us to amplify and detect any new genomic sequence in any sample.

Virologist Miguel Ángel Jiménez Clavero collects on his Twitter account (@virus merger) some examples New viruses discovered in recent years:

Discovery of new viruses occurs anywhere in the world (Mexico, USA, Peru, Sudan, China, Uganda…) and the common feature is that they all come from the animal world, they are zoonotic: sudden animal diseases. human or vice versa. They are the things we can say zoonotic rashes.

The new Langya virus was discovered during a routine epidemiological surveillance study. This consisted of recruiting patients with a history of fever of unknown origin between April 2018 and August 2021 at three hospitals in eastern China’s Shandong and Henan provinces. Throat swab samples were taken and the entire sequence was sequenced. sample.

Detection was accomplished by metagenomic methods (total RNA extraction, sequencing, sequence alignment and splicing) and virus isolation. The first patient whose genome was found was a 53-year-old woman living in the city of Langya; That’s why it’s called the Langya virus.

Over the three years of the study, researchers found 35 people infected with Langya. Often farmers exposed to animals in the month before their symptoms, ranging from severe pneumonia to cough, appear. The most common symptoms were fever, cough, and fatigue. The only potential pathogen found in 26 of 35 patients was Langya virus.

No deaths have been identified, so it does not appear to be fatal to humans at this time. There was no link or epidemiological relationship among the 35 patients. No cases in the same family or in geographically close locations. There are no data to suggest human-to-human transmission. For all these reasons, this cannot be considered a specific epidemiological epidemic. It is a retrospective study of isolated cases over three consecutive years.

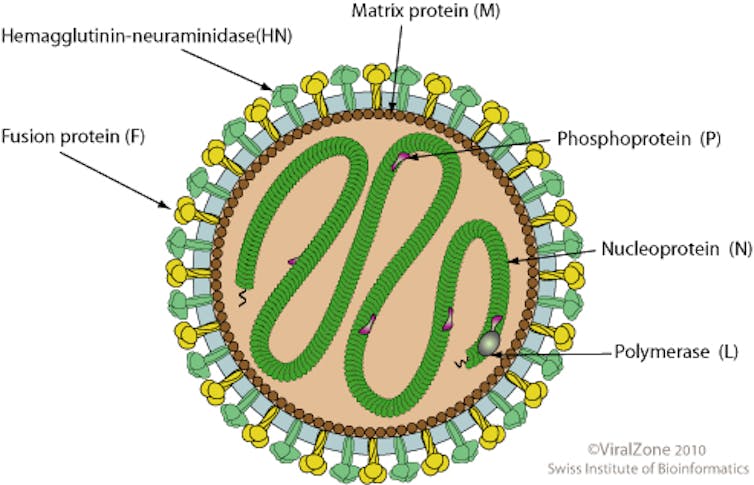

Langya’s genome shows that the virus is closely related to Mojiang henipavirus, which was first isolated from rats in an abandoned mine in southern China’s Yunnan province in 2012. Henipaviruses belong to the Paramyxoviridae family, which includes measles, mumps, and many other respiratory viruses. infecting people.

Other henipaviruses have been discovered in bats, rats and shrews from Australia to South Korea and China. The only henipaviruses known to infect humans so far were Hendra and Nipah viruses, which cause respiratory infections and can even be fatal.

To determine the possible animal origin of this virus, the researchers analyzed the presence of antibodies to the virus in the blood of 168 goats, 79 dogs, 112 pigs and 100 cows living in the villages of infected patients. Only 4 dogs and 3 goats tested positive.

They also took tissue and urine samples from 25 small wild animal species to investigate the presence of the virus genome using molecular techniques. After analyzing a total of 3,380 samples, they detected virus RNA in 27% of the 262 shrews examined (not in all species; particularly lassiura crocidura Y Crocidura shantungensis). These data suggest that perhaps such shrews may be the reservoir or repository of the virus, able to infect humans directly or through other domestic animals, and humans may be an accidental host.

There is no cause for alarm at this time as there are no data or indications that this new virus could pose a pandemic threat. What the article highlights is the need for a global surveillance system to detect the indirect effects of new viruses. We don’t know when the next pandemic will happen – covid-19 was not the last (yet) nor the worst (could be far more deadly) – but what we are sure of is that there will be another pandemic. and it will most likely come from the animal kingdom.

In the near future, the only possible strategy may be based on concept alone. One Health (one health or global health), surveillance and coordination of efforts in human health, animal health and environmental health. Knowing what’s going on in the animal world will protect us from future threats.

A version of this article was originally published on the author’s blog microBIO..![]()

Ignacio López-Goñi, Professor of Microbiology, university of navarra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original.

Source: El Nacional

Alice Smith is a seasoned journalist and writer for Div Bracket. She has a keen sense of what’s important and is always on top of the latest trends. Alice provides in-depth coverage of the most talked-about news stories, delivering insightful and thought-provoking articles that keep her readers informed and engaged.