It is an important part of the mosaic in New Testament history and is one of the oldest textual witnesses of the Bible: a small manuscript fragment of a Syriac translation written in the 3rd century and copied in the 6th century. A researcher from the Austrian Academy of Sciences discovered the piece using ultraviolet photography.

About 1300 years ago, a scribe in Palestine took a Bible book with Syriac text on it and deleted it. In the Middle Ages, parchment was scarce in the desert, so manuscripts were often erased and reused. A medievalist from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW) has now managed to restore the legibility of the lost words in this multi-layered manuscript called the parchment: Gregory Kessel has discovered one of the oldest translations of the Bible. It was copied in the 3rd century and 6th century on some preserved pages of this manuscript.

One of the earliest fragments to testify to the Old Syriac version

“The Syriac Christian tradition knows several translations of the Old and New Testaments,” says medievalist Gregory Kessel. “Until recently, only two manuscripts were known containing the Old Syriac translation of the Bible.” One of them is now in the British Library in London, while the other was found as a scroll in Saint Catherine’s Abbey on Mount Sinai. Fragments of a third manuscript were recently identified by the Sinai Palimpsests Project.

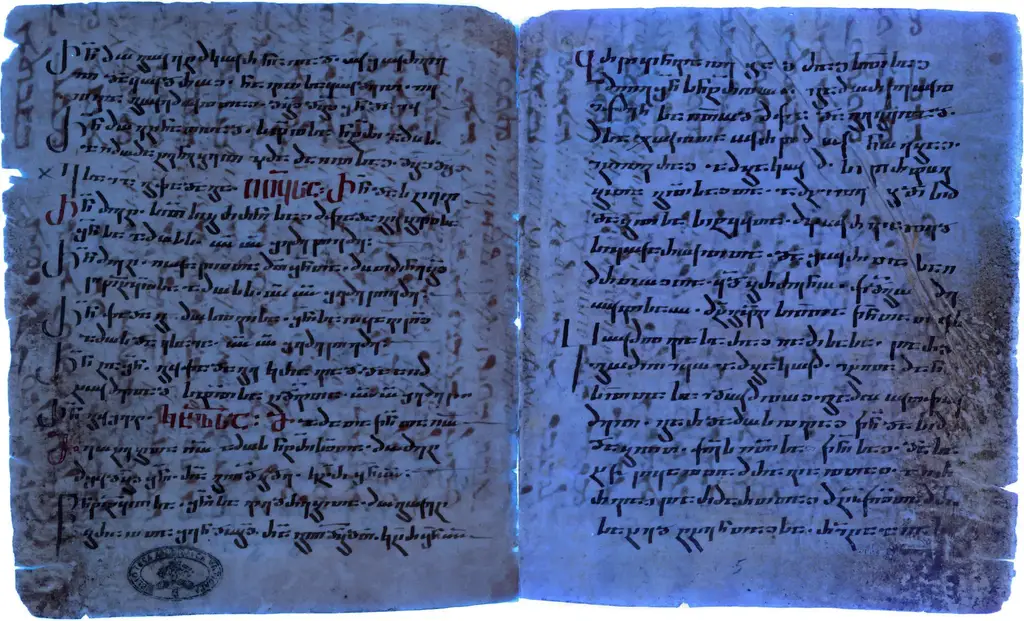

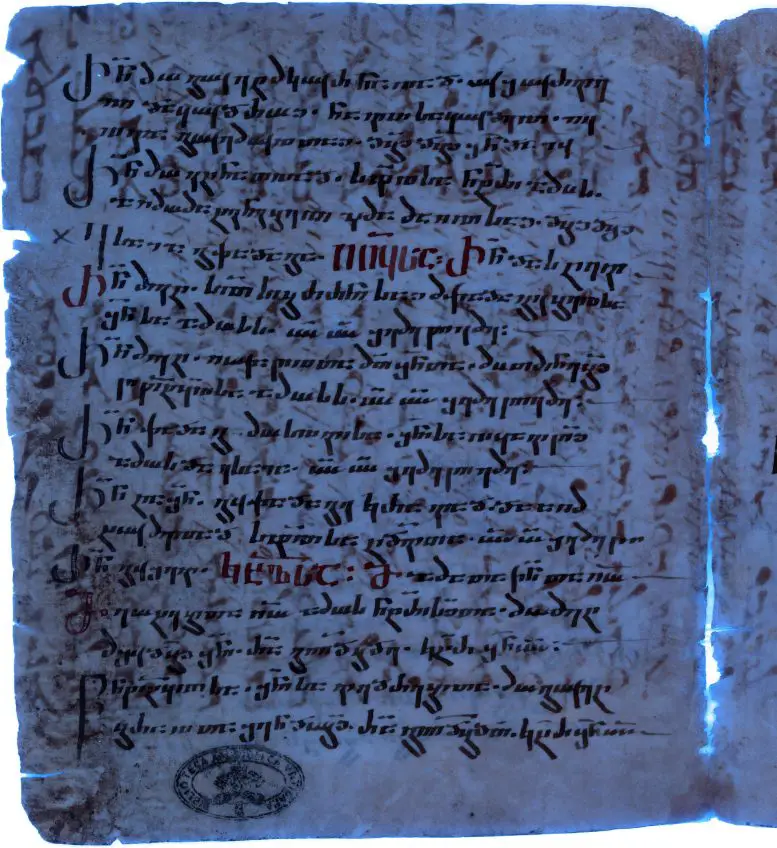

Part of the translation of the New Testament can be seen under ultraviolet light. Copyright: © Vatican Library

A small fragment of the manuscript, which can now be considered the fourth textual witness, was identified by Gregory Kesel as the third text layer, the double scroll, in the Vatican Library manuscript, using ultraviolet photography. This fragment is the only known remnant of the fourth manuscript confirming the Old Syriac version and opens a unique path to a very early stage in the history of the textual transmission of the Bible. For example, the original Greek text of the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 12, verse 1, states: “Then Jesus passed through the fields on the Sabbath; and his disciples were hungry, and they began to gather and eat ears of corn,” is the Syriac translation that says: “[…] they began to gather the ears, rub them with their hands, and eat them.”

A Syriac translation before the Codex Sinaiticus

Claudia Rapp, director of OeAW’s Institute for Medieval Studies, is also pleased: “Grigory Kessel, with his deep knowledge of the Old Syriac texts and features of writing, has made a great discovery.” The Syriac translation was written at least a century before the earliest surviving Greek manuscripts, including the Codex Sinaiticus. The oldest surviving manuscripts with this Syriac translation are from VI. century and preserved in the erased layers of newly written parchment pages, the so-called palimpsests.

“This discovery proves how fruitful and important the interaction between modern digital technologies and basic research can be when working with medieval manuscripts,” says Claudia Rapp.