After lightning struck a tree in the New Port Richey area, a University of South Florida professor discovered that the lightning had caused a new formation of phosphorous material. It was found in rock – the first time it was found in solid form on Earth – and may be a member of a new mineral group.

“We’ve never seen this material occur naturally on Earth – minerals that can be found in meteorites and in space, but we haven’t seen this exact material anywhere,” said geophysicist Matthew Pasek.

In a recently published study Communication World and EnvironmentPasek explores how high-energy events such as lightning can trigger unique chemical reactions, in this case leading to a new material that switches between space minerals and found minerals. on earth.

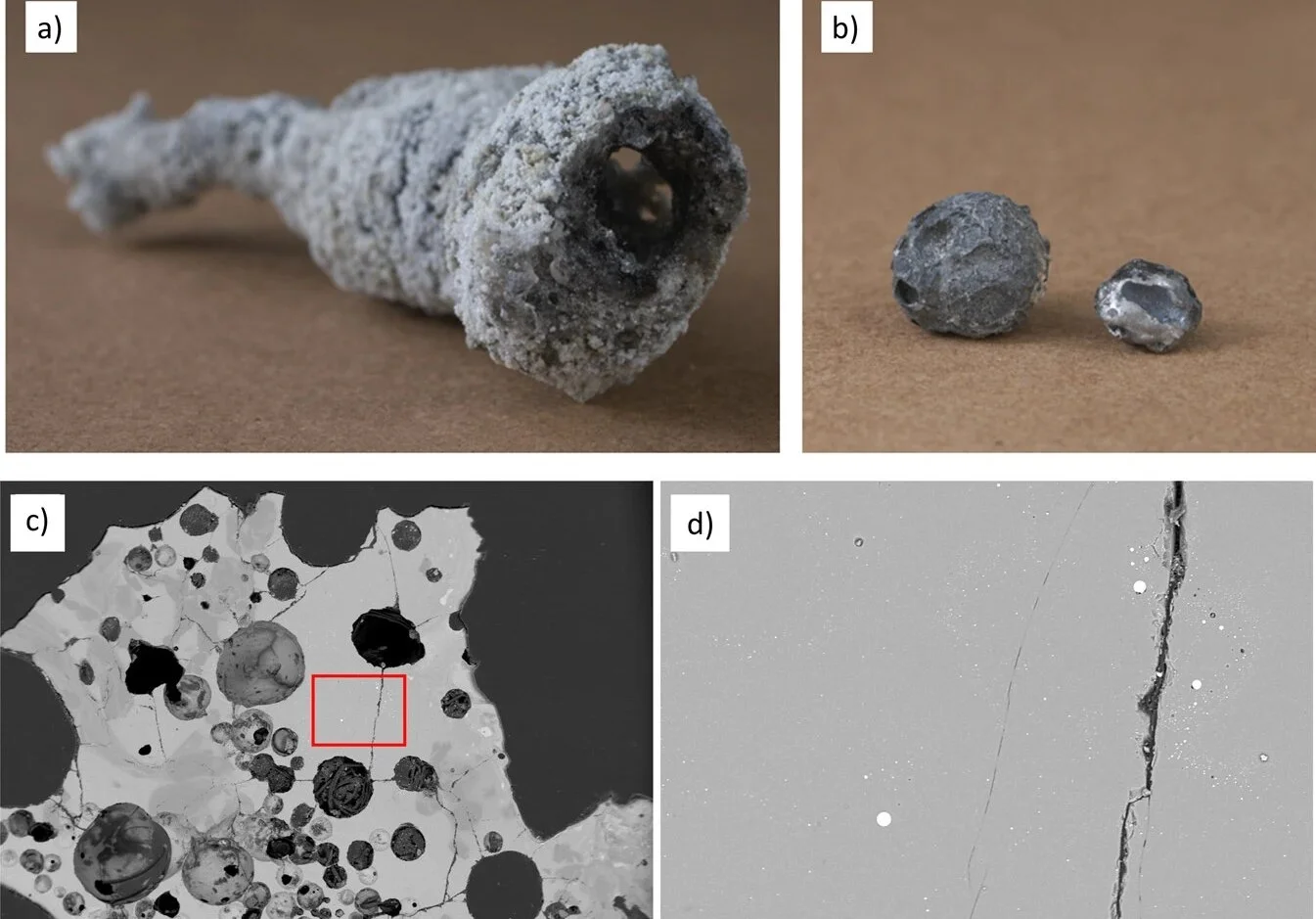

“When lightning strikes a tree, the ground typically explodes and the surrounding grass dies, sending an electrical discharge into nearby rocks, soil and sand, forming fulgurites, also known as ‘fossilized lightning’,” Pasek said.

When the New Port Richey homeowners discovered a “lightning mark,” they found fulgurite and decided to sell it, believing it to be valuable. Pasek bought it and began collaborating with Luca Bindi, later professor of mineralogy and crystallography at the University of Florence in Italy.

Together, the team decided to investigate unusual minerals containing the element phosphorus, specifically those formed by lightning, to better understand the high-energy phenomenon.

“It’s important to understand how much energy lightning has, because then we know how much damage an average lightning strike can do and how dangerous it is,” Pasek said. Said. “Florida is the lightning capital of the world, and lightning safety is important: if lightning is powerful enough to melt rocks, it can certainly melt people too.”

In humid environments like Florida, iron often builds up and coats tree roots, Pasek says. In this case, the lightning strike not only burned the iron in the roots of the tree, but also burned the natural carbon in the tree. The two elements caused a chemical reaction to form fulgurite, which looked like a metal “lead”.

The colored crystalline substance in fulgurite has revealed a material that had never been discovered before.

Associate principal investigator Tian Feng, a graduate of USF’s geology program, attempted to process the material in the lab. The experiment failed, showing that the material likely formed rapidly under certain conditions and would decompose into the mineral found in meteorites if heated for too long.

“Previous researchers show that flash phosphate depletion was a common phenomenon on early Earth,” said Feng. “However, there is an environmental phosphide reservoir problem on Earth where it is difficult to recover these hard phosphide materials.”

Feng says this research may reveal the possibility of other reduced forms of minerals, many of which may be important to the development of life on Earth.

According to Pasek, given the rarity of its natural source, this material is unlikely to be mined for uses similar to other phosphates, such as fertilizer. However, Pasek and Bindi plan to continue researching the material to determine whether the material can be officially declared a mineral and to raise greater awareness of the scientific community.