Scientists have found a new way to levitate water

- June 8, 2024

- 0

If you drop a handful of droplets into a very hot pan, you can watch them jump and dance. Believe it or not, these drops actually float. If

If you drop a handful of droplets into a very hot pan, you can watch them jump and dance. Believe it or not, these drops actually float. If

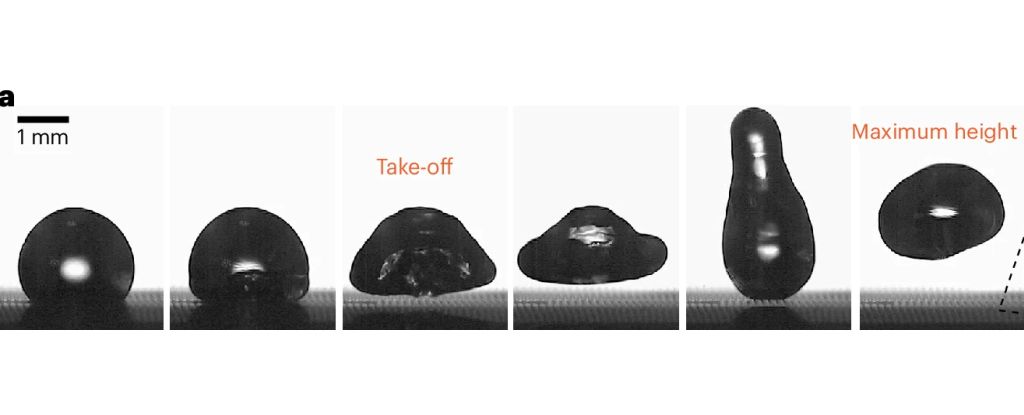

If you drop a handful of droplets into a very hot pan, you can watch them jump and dance. Believe it or not, these drops actually float. If the surface is hot enough, the heat vaporizes the side of the drop closest to it, creating a cushion of gas on which the rest of the drop floats. This phenomenon is known as the Leidenfrost effect, after Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost, a German physician who documented this phenomenon in the 18th century.

Now a team of scientists has developed a way to lower the temperature at which this little dance of water occurs. A microscopically textured surface transfers heat to the droplets more efficiently, and this discovery has important implications for heat transfer applications such as the cooling of industrial equipment and nuclear cooling towers.

“We thought micropillars would change the behavior of this well-known phenomenon, but our results defied even our imagination,” says Jingtao Chen, a mechanical engineer at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

“The observed bubble-droplet interaction is a major breakthrough in boiling heat transfer.”

We have known about the Leidenfrost effect for some time and its parameters are well understood. For this to happen, there needs to be enough heat for the water to evaporate instantly when it comes into contact with the hot plate, but not so much heat that the entire water droplet evaporates instantly.

The reason water does not evaporate completely at Leidenfrost temperatures is because most of the energy from the hot surface dissipates as vapor rather than entering the rest of the droplet.

The surface developed by Cheng and his colleagues consists of hundreds of tiny pillars about 0.08 millimeters high, about the size of a human hair. They are located in a grid shape at a distance of approximately 0.12 millimeters. When placed on the surface, a drop of water covers approximately 100 columns.

As the water rises to the surface, the columns apply pressure to the water droplet, providing more heat to the interior and allowing the water to boil faster. This means that the Leidenfrost effect can be observed within milliseconds and at much lower temperatures than on a flat surface such as a stove or pan.

In fact, the team was able to get Leidenfrost levitating at 130 degrees Celsius, much lower than the 230 degrees Celsius they typically estimate for impact under these conditions.

Now water is a great cooling tool. Water boils and evaporates at about 100 degrees Celsius (varies slightly with altitude). Since liquid water turns into steam, it cannot get hotter than this boiling point. This is why this person cooks soup in a plastic bag over the fire: The heat is transferred to the water, which cannot exceed the melting point of the plastic.

The micropillar surface therefore offers a more efficient heat transfer mechanism that could be much safer than water cooling technologies currently in use, helping to prevent dangerous accidents such as steam explosions, the researchers say.

“Vapor explosions occur when vapor bubbles in a liquid expand rapidly. [наявність] There is an intense heat source nearby. An example of where this risk is particularly relevant is in nuclear power plants, where the surface structure of heat exchangers can affect vapor bubbles. “It can grow and potentially trigger such eruptions,” says Wen Huang, an engineer at Virginia Tech University.

“Through our theoretical research in the paper, we investigate how the surface structure affects the growth mode of vapor bubbles and provide valuable information on controlling and reducing the risk of vapor explosion.” The team’s research was published on: Natural Physics.

Source: Port Altele

As an experienced journalist and author, Mary has been reporting on the latest news and trends for over 5 years. With a passion for uncovering the stories behind the headlines, Mary has earned a reputation as a trusted voice in the world of journalism. Her writing style is insightful, engaging and thought-provoking, as she takes a deep dive into the most pressing issues of our time.