A monumental burst of oxygen was thought to have triggered the Cambrian explosion around 540 million years ago, breathing life into Earth’s biosphere and giving rise to a rich array of highly complex animal species.

However, the question of whether oxygen really played such a significant role is hotly debated, as other factors could have potentially triggered the biggest explosion in Earth’s evolution, from the near-collapse of Earth’s magnetic field to the erosion of the Gondwana Plateau, asteroid dust, and even marine worms.

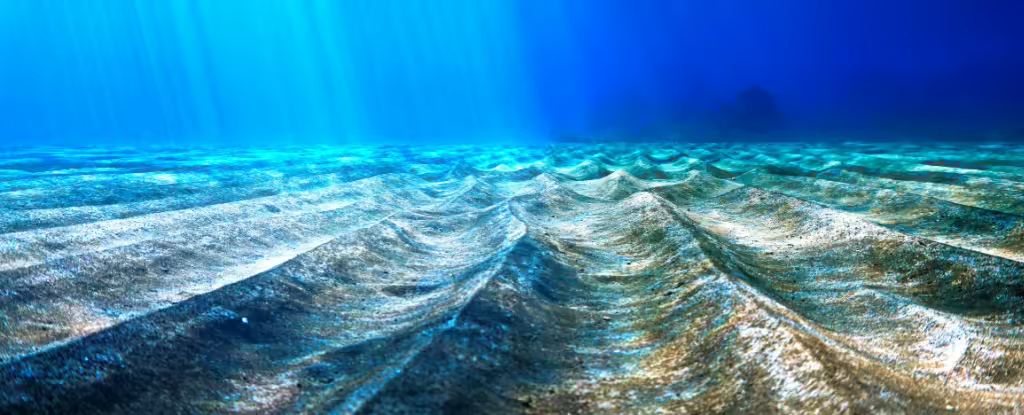

Now, new research looking at the geological record from around the world shows that half a billion years ago, oxygen was not filling the atmosphere and oceans, with most of it slowly dissolving into shallow basins and ocean shelves. That doesn’t mean oxygen played no role in the explosion of biodiversity that gave rise to all the weird, crazy, and wild creatures we see today.

“Cambrian animals probably didn’t need as much oxygen as scientists had previously thought,” says Eric Sperling, a geobiologist at Stanford University and senior author of the new study. “We found a small increase in oxygen saturation” in sedimentary rocks that formed at the bottom of ancient oceans, “large enough to cause major changes in ecology.”

Scientists have reasoned that without sufficient oxygen, single-celled organisms and other small creatures that began to exist before the Cambrian explosion would not have been able to significantly increase their size and expand their body plans. But scattered and sometimes conflicting data from different geological regions around the world has led some to question how much oxygen is actually needed and whether oxygen levels in many habitats exceed critical thresholds, possibly suppressing life.

The team behind this new study believe they have reconciled some of these discrepancies through statistical analyses of trace metals preserved in sedimentary rocks, thereby helping to reconstruct long-term trends in global ocean oxygen levels and marine life over the past 700 million years of Earth’s history.

Analyses of two trace metals, molybdenum and uranium, both of which are indicators of global ocean oxygen levels, together with biogeochemical models of oxygen flow between the oceans and the atmosphere, suggest that deep ocean oxygen levels reached today’s levels only 140 million years after the Cambrian explosion in the Devonian period.

“Globally, we didn’t see the oceans fully oxygenated to today’s levels until about 400 million years ago, when we see large forests emerging on land,” explains Richard Stokey, a palaeobiologist at the University of Southampton. “Who led the study?

However, in shallow waters, oxygen levels caused by wind and waves can rise high enough to support all kinds of marine life.

“This is not a huge increase in oxygen, but based on what we see in naturally low-oxygen areas today, it may be enough to exceed critical ecological thresholds,” Sperling notes.

The team’s findings expand on the results of a 2017 study that showed shallow seas were initially saturated with oxygen, but that atmospheric oxygen did not reach modern levels until the subsequent Ordovician period, 50 to 100 million years after the Cambrian explosion.

However, other recent studies have shown that oxygen levels began to rise in the early Ediacaran period, around 640-600 million years ago, during the first of three successive oxygen pulses that coincided with major evolutionary leaps leading up to the Cambrian explosion. Meanwhile, other researchers argue that oxygen levels in deep time were so variable that it is difficult to say what effect they had on the development of biodiversity. The study was published in: Natural Geology.