For centuries, Christian pilgrims have spoken of the masterfully decorated altar, erected by Crusaders in the mid-12th century in the heart of the Holy Land. But it disappeared unexpectedly in the 19th century. Here’s how it was found.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also known as the Church of the Resurrection of Jesus, is located in Jerusalem on the site where Jesus was crucified and buried. There, according to Christian scriptures, he was resurrected. At the time of his execution, the hill of Golgotha and the cave containing the empty tomb were located outside the walls of the ancient city (now the Christian quarter of Old Jerusalem).

The early Christians considered this place sacred, and the memory of it did not fade even after the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus in the First Jewish War in 70. In the 4th century, the Holy Land was visited by the Byzantine queen Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine I. There she had an epiphany and at almost 80 years old began the field we now call archaeology.

The main excavation site was Golgotha. Christian sources claim that during her explorations Elena found the cave where Jesus was buried, the cross on which he was crucified, four nails from the cross, and other elements related to the concept of the “Passion of Christ”.

After such findings, the queen archaeologist began to study architecture. During her lifetime, churches began to be built in places important to Christians. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is a complete complex with separate markings of the crucifixion, burial and cross sites. Its construction was completed in 335 in honor of Emperor Constantine’s visit to Jerusalem.

In 614, Jerusalem fell to the Persian king Khosrow II. He took care of the Christian shrines. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was damaged during the siege, but was later restored. The situation remained the same under Muslim rule. Christian pilgrims visited the Holy Land relatively freely until early 1009, when Caliph Al-Hakim Biamrillah permitted the massacre of Christians in Jerusalem and the destruction of their temples.

This violation of centuries-old agreements was one of the major causes of the First Crusade. It began in 1096 and ended with the capture of Jerusalem on July 15, 1099. Having killed a large part of the city’s population (including Christians who had survived the Islamic massacre), the crusaders began to restore the temples.

The Christian kings still had enough money, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was rebuilt on a grand scale. It was consecrated on July 15, 1149, exactly 50 years after the Crusaders had conquered the Holy City and established the Kingdom of Jerusalem. This time, the temple was built in the Romanesque style, with the main altar in the middle.

Stories about this beautifully decorated altar were left by pilgrims in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. But then the altar disappeared. Perhaps this happened during the fire of 1808, which damaged part of the temple. For two hundred years in a row, the crusaders’ altar was thought to be lost. They found it by pure chance.

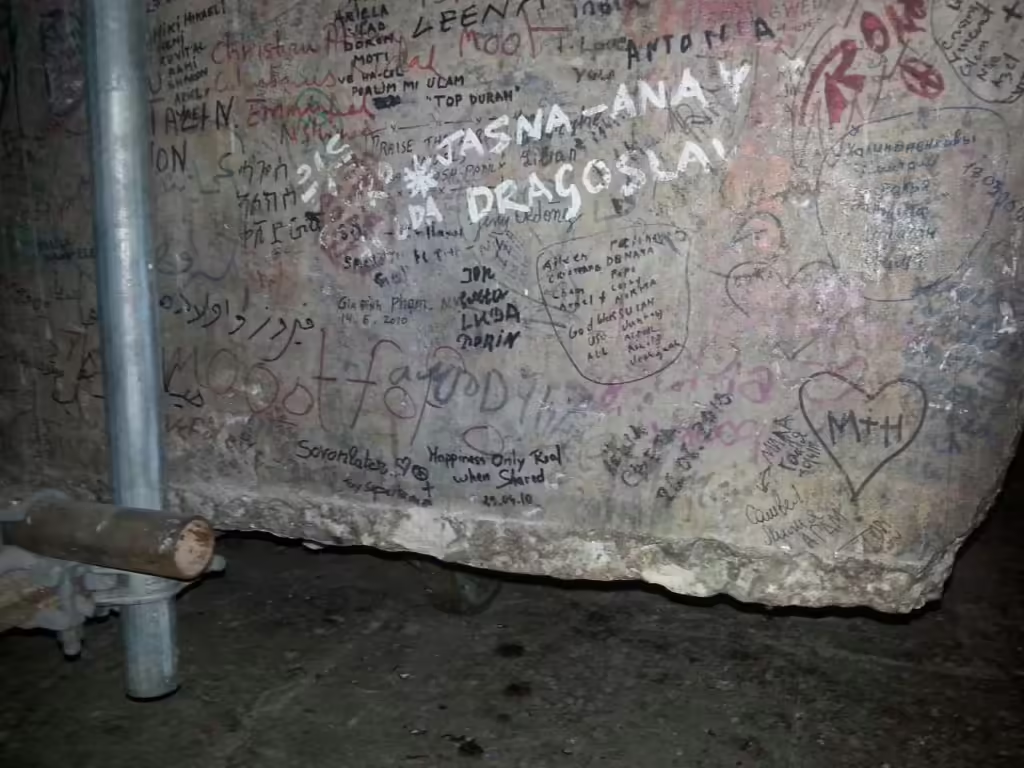

It is worth noting that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is constantly being studied by scientists of various specialties, from archaeologists to religious scholars. Thousands of pilgrims and tourists visit here every year. But only this year, archaeologist Amit Re’em from the Israel Antiquities Authority and historian Ilya Berkovich from the Austrian Academy of Sciences wondered what a strange stone slab weighing several tons was standing in the back corridor of the temple. Tourists used it for traditional inscriptions in the style of “Kisa and Osya were here.”

When the slab was turned over, it turned out that the other side was covered with marble mosaic made with the unique cosmatesco technique. Invented by masters from the Italian Cosmati family, this technique did not go beyond their family circle. They created a mosaic made of the smallest pieces of marble of different colors.

The result was a marble thing, as if carved from a single piece of rock, but with a man-made pattern. From the very beginning, the Kosmati masters worked under the orders of the Holy See.

Only a few works of art in the Cosmatesco style were known outside Rome, and so far only one exists outside Italy: in Westminster Abbey in London, where the Pope sent one of his masters.

The discovery of an altar decorated with Kosmatesco mosaics in Jerusalem can mean only one thing: the lord of the Kosmati family came there on the personal orders of the Pope. Not only was it expensive, but it was also very honorable. The Holy Catholic Church still considered the Crusade to be an extremely successful idea and demonstrated its position in all possible ways.