Jaime Charis: When you give something in a lab, you feel satisfied…

- July 19, 2022

- 0

| Ramses Romero In Palmar de Varela, a small Colombian town on the banks of the Magdalena River, a boy grew up with dreams of becoming a great

| Ramses Romero In Palmar de Varela, a small Colombian town on the banks of the Magdalena River, a boy grew up with dreams of becoming a great

In Palmar de Varela, a small Colombian town on the banks of the Magdalena River, a boy grew up with dreams of becoming a great doctor. The son of a family living together long enough on his country’s north coast, in 1978, when he was just 19 years old, he decided to pursue his life purpose up to that point. He tried to study medicine in Colombia, but was unsuccessful. He decided to emigrate. Just. His first and only option was Venezuela.

He arrived in Caracas with more suspicion than certainty. He settled in Catia at the house of a relative. But as an immigrant he had to work to survive, and medicine was a profession that would take up all his time. He wanted to be a scientist devoted to health, and at that time Pharmacy was the option that convinced him the most. He enrolled in the night shift at the Universidad Santa María school so that he could work during the day.

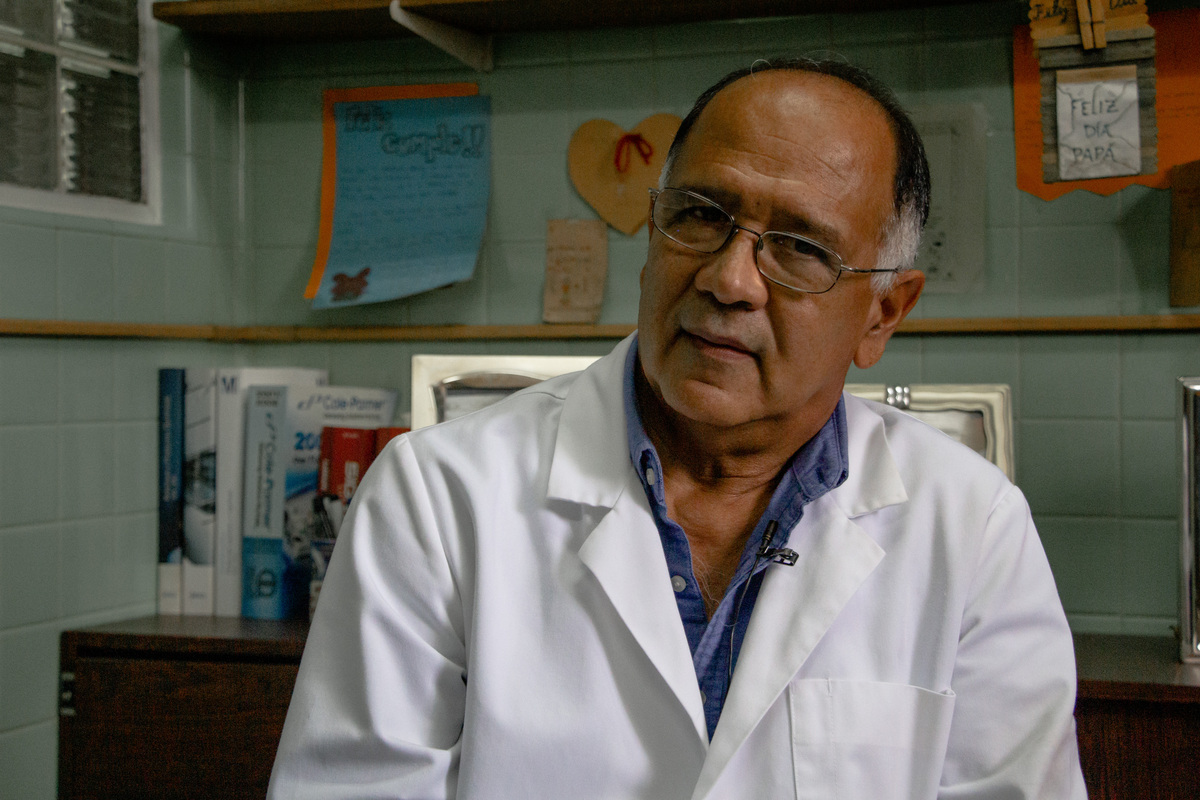

More than forty years have passed since then, and Jaime Charris has enjoyed a prestigious career as a researcher supporting the medical field in the study of the pharmacological properties of new compounds with therapeutic potential, awarded the Lorenzo Mendoza Fleury Prize.

He has good memories of his student days. 1979 Caracas was very different from today. There was a lot of security. He remembers forming study groups with other classmates and meeting them in the corridors of the Central University of Venezuela or in Los Próceres, where they could stay until dawn, something now hard to imagine. “It was a very pleasant time and we were living quietly.”

In 1985, just as he was finishing his degree, Professor of Organic Chemistry Dr. Eliodoro Palacios, along with another colleague, chose him to pursue a master’s degree in Pharmaceutical Chemistry at UCV. At that time, the University of Santa María planned to set up a facility at its La Urbina headquarters to develop active ingredients to make drugs. Upon completion, he did his master’s and doctorate, as the project was not finished yet. “There I started working with Dr. José Nicolás Domínguez, my professor at the Faculty of Pharmacy, who trained and guided me and introduced me to the field of parasites,” Charris recalls.

After finishing his studies, his aim was to establish contacts with international research groups. His first opportunity was at the San Juan de Dios Hospital in Bogotá, where he worked on the synthesis of the Malaria vaccine by Dr. Interned with Manuel Elkin Patarroyo’s team.

He then contacted a group of researchers working in the field of diseases such as parasites, Leishmania, Malaria and African Trypanosoma in Atlanta, United States, and contacted a group in and out of France through a graduate training program. worked on cancer. “That’s the dream of all of us who work here: to seek new horizons that open you up, help your intuition, create, and be more creative in what you do,” she says.

He adds: “These experiences have allowed me to see research from another perspective. While not Nobel Prize winners, they are well-known groups and individuals who work hard and teach you to see things differently here, in the country.

For Charris, a pharmacist who graduated from Universidad Santa María and is a professor in the Faculty of Pharmacy of the Central University of Venezuela, the Lorenzo Mendoza Fleury Award is, beyond recognition, an incentive to continue developing research projects to solve certain problems. affects society both nationally and regionally. In the case of your field of study, some parasite or cancer-like disease.

“This makes me very proud because it forces one to keep working. Actually, I am retired, but I am active not only with national groups but also in my projects. I also train human resources, aid staff, I have graduate students, especially PhDs”, the 63-year-old researcher proudly says.

As a researcher, Charris combines her work with teaching. He has been a professor at the UCV Faculty of Pharmacy since 2007, teaching Organic Chemistry and has also been a thesis instructor for students from different universities in the country. Although he is still retired, he continues to give postgraduate courses and develop projects as a researcher.

«As they say there, to be a good teacher you have to be a good researcher. Teaching and research are roles that go hand in hand, you need to be constantly in the process of updating, reading literature and writing articles to stay current,” he assures.

The researcher is worried about the student and professor desertion, especially at the UCV Faculty of Pharmacy, where his office is located. There he spends several hours a day researching, writing or reading a scientific paper. “While the number of applications to select 200 used to be 1,200, today the number of applications barely reaches 300. This capitalization of human resources is seen not only at the student level, but also among teachers. Incentives are not what they used to be.

It is difficult for the chemist to say which role he feels more comfortable in as he enjoys both equally. “I feel comfortable with both, but you feel accomplished when you intervene on the spot for problems that arise at the lab level,” he says. Charris admits that there are very few researchers left in the country and emphasizes that those who do can’t stop. “We need to try to provide insight that will enable us to overcome conditions that are experiencing an upswing like malaria,” he says.

Charlie divides his time between the classrooms and the lab. Between blackboards and test tubes. Before reaching its small office, you have to pass through one of the laboratories of the Faculty of Pharmacy. Image destructive. The scales are covered in plastic to protect them from dust and dirt from the one and a half year renovations at UCV. Infrared equipment is damaged and reagents are insufficient.

But reality doesn’t stop him. He works on various chemical reactions for several research in a small space. There, he wrote on a glass surface the formulas of the organic compounds he was working on, and several beakers with reactions.

For several years now, the chemist has been working on repositioning molecules used for conditions unrelated to parasitosis. “By making small changes I can make them have an effect on Chaga disease, Leishmania or Malaria. In this case, what I’m doing is trying to see them, try them out, see how they work, and if all goes well I try to change it up to see how I can improve the effect,” she explains.

The chemist ensures that difficulties are always present when developing a research project; however, they are now concentrated. “There are problems in obtaining reagents and the equipment is already old. It is no longer working and researching like it used to be abroad. Sometimes you have to turn to friends or colleagues abroad for support,” he says.

Charris says the situation has intensified since 2016. He adds that since 2013, UCV has not funded projects. However, it indicates that the work must continue. “You can’t stay too long to do anything, you have to find a way to overcome the challenges that come up and we’ve made it so far,” he says.

Among the most important contributions of his professional career, Charris highlights the training of both undergraduate and graduate students and the findings in the study of quinoline and nitroimidazole to treat conditions such as Malaria or Leishmania, respectively. «The core of metronidazole, used in the treatment of gastrointestinal conditions, does not have leishmanicidal activity, especially in cutaneous Leishmania, which a group in the Vargas Hospital Biomedicine field is working on. We took this metronidazole and made some simple modifications and found that activity on cutaneous Leishmania in mice resulted in a 93% cure in terms of elimination of the parasite at skin level and in between. almost 63% and 70%”, he elaborates.

Although the results are positive, the chemist assures that there is still a long way to go to fulfill every researcher’s dream: application in humans. “What we’re looking for with this project is to go beyond mice, we want to see if it produces any side effects. We are in the process of synthesizing the largest number of compounds to perform these studies. We want to see if we can reach the preclinical stage, stages I, II, III, until we get to a drug. “But that takes time. It’s an advantage that metronidazole is an applied drug,” says Charris.

Beyond her role as a researcher and teacher, Charris enjoys her family life, which is such an important part of it. In her office, in the library, there are several photo frames with photos of her daughters and a handcrafted letter from a past school stage that reads “Happy Birthday Dad.” The chemist is married to Judith Pedroza, a pharmacist like him, and they have three daughters who give him two grandchildren. “Because I come from the beach, I really like to go to the beach and enjoy a nice barbecue with my family. Sometimes we go to Higuerote and spend weekends there».

In her spare time, she enjoys exercising in her lab at the UCV School of Pharmacy, when she is not working on a reaction or writing an article. He often goes jogging for health. Part of the UCV Teachers’ Association football team happily comments.

He also loves cooking, especially seafood. “My wife makes breakfast, I cook lunch. I love to experiment in the kitchen, I invent,” she says.

In more than 40 years in Venezuela, Jaime Charris feels more Venezuelan than Colombian. “I am already a foreigner in Colombia. I go once in a while, once every two years, but when I’ve been there for two weeks, I want to go back,” he says with a laugh.

He feels very grateful to the country and its people who opened their arms to him. “This country is beautiful. When I came, I feel like I have to repay everything it gave me. Venezuela gave me the opportunity to grow,” he says. He is not afraid of death, he finds peace with the thought that one day he will not be here. I told my wife that when the time came, they would burn me, take my ashes to the Magdalena River and leave me there.”

Source: El Nacional

Alice Smith is a seasoned journalist and writer for Div Bracket. She has a keen sense of what’s important and is always on top of the latest trends. Alice provides in-depth coverage of the most talked-about news stories, delivering insightful and thought-provoking articles that keep her readers informed and engaged.