In the 1980s, amid the heated debate about collapse and overpopulation, economist Julian Simon became famous for the notion that the last resort was neither oil, nor uranium, nor water: humanity’s last resource was imagination. For the North American thinker, every human being born was more than a mouth to feed, it was above all a mind for generating ideas and solving problems.

Now that more experts are convinced that world population growth is about to sink, the idea that we need more people becomes more relevant than ever. First of all, the possibility of conceiving people on an industrial scale is closer than ever.

From the machine that makes man…

It will be a century since JBS Haldane, one of the most important British geneticists in history, coined the term ‘ectogenesis’ to describe pregnancies that will take place in these artificial wombs. Just then, Haldane predicted that by 2074, less than 30% of pregnancies would be ‘natural’. far yes; but it’s getting closer every day (and it’s still 50 years away).

Currently, the viability line of human fetuses is around the 22nd and 23rd weeks of pregnancy. This is when the lungs develop, and it remains a critical point even today. The numbers speak for themselves: while only 20% of those born at 23 weeks survive, when we talk about those born at 25 weeks, that figure rises to 80%.

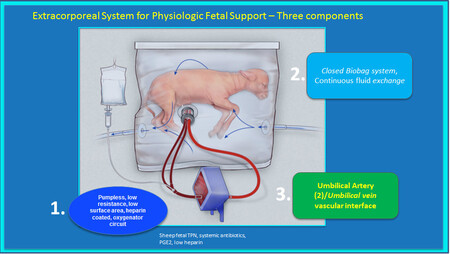

This is a critical point, among many other things, because of the technical complications inherent in it: as Matt Kent explains, simple things like pumping blood to very immature fetuses are a first-level technological problem, needing a pressure that tissues cannot withstand. well. Improving our ability to reduce deaths (and their sequelae) caused by premature births (one in ten pregnancies in the US today) is necessary, but also very difficult.

There are challenges on the other side of the process (from zygote to fetus) but we are slowly making progress. There are examples for every taste. To review a few recent ones: Professor Yoshinori Kuwabara of Juntendo University in Japan and his team were able to impregnate goat embryos in a machine with tanks filled with amniotic fluid; or Professor Helen Hung-Ching Liu of Cornell University’s Center for Reproductive Medicine has managed to nearly complete the development of a mouse embryo thanks to a bioengineered endometrium.

The medical benefits are clear: This technology could help couples struggling to conceive or premature babies survive. Pregnancy and childbirth are extremely difficult processes. and many theorists already refer to the termination of natural pregnancy as ‘humanity’s last great salvation’. But above all, it could represent one of the greatest social, educational and health developments in decades.

‘Ectogenesis’ can provide safe and healthy pregnancy environments free from pollutants, drugs and alcohol. Martha J. Farah, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, has studied the relationships between brain development and socioeconomic status for many years. Generalization of ectogenesis eliminating one of the biggest sources of inequality existing: pregnancy conditions.

…to the man-made factory

Kibbutz Gan Shmuel Children’s Home (1935-40)

Paradoxically, this is all the easy part of “creating people”. As Scott Alexander said years ago, for many contemporary problems, “society is fixed, biology is variable.” Or, bringing it to the point of the article, imagine that we finally perfected these technologies and developed the ability to industrially produce humans as a way to reverse current demographic trends or populate interplanetary colonies. What do we do with hundreds, thousands or millions of babies? How do we train them, how do we train them, how do we turn them into functional beings?

Here, to be honest, the unknowns are much larger. And not because there are no modern precedents, but because those precedents fail. I think of the famous “children’s houses” of Israeli kibbutz. Until the 1980s, the prevailing method of education in collective Zionist communities involved leaving children in community centers from the moment they were born. There, it was about applying the basic ‘principle of equality’ in the operation of the kibbutz in those ‘children’s homes’.

In this sense, “the kibbutz’s educational authority was responsible for the upbringing and welfare, food, clothing, and medical treatment of all children born in it”. Children may spend two or three hours a day at their parents’ homes, but most of their lives are spent in the Children’s Home and the common areas of the kibbutz. While this system was ubiquitous until the 1980s, “family-friendly” trends eventually threw it into the dustbin of history and today it’s just an old memory. Moreover, many people even find it repulsive.

Are we ready for the revival of the great orphanages of the nineteenth century? Will we have the capacity to educate and give opportunities to the millions of people these theoretical factories can take to the streets? The question is relevant because it is not even clear that the arrival of this type of technology will have a significant impact on current demographic trends.

What Demographer Lyman Stone drew attentionThe transition to lower fertility rates could have been around 1500 or 1300 or 900 or 500 BC; in fact, it probably took place in various places during these periods, but because this did not happen at the same time as the great economic growth. Improving living standards, improving children’s survival, and compensating for population losses from falling fertility was never pursued.”

So, about that a much deeper problem (and has its roots in culture, productivity, and social relations) that such a technological solution turns them around. At least on his own. But if Julian Simon is right, and if the best way to build a better future for ourselves (on or off Earth) is to become more minds thinking together, we should start thinking about it. Demographic winter may be imminent, but to win the game we will have to change a lot of things that make up what we now call civilization.