This article was written by Laurent Palk, Senior Lecturer at the National Museum of Natural History, and published on The Conversation. 24 Channels translates and publishes in an adapted form.

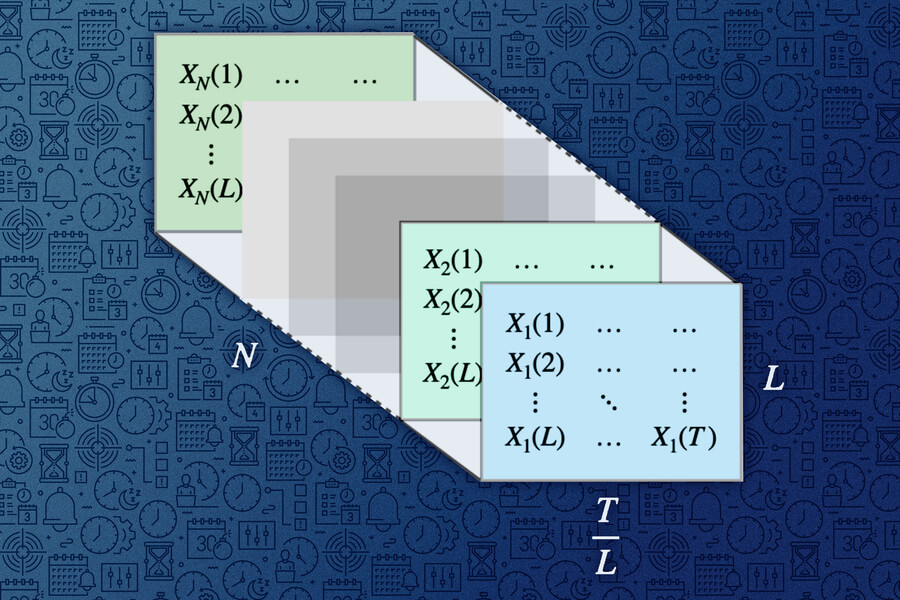

Task details

The Beresheet mission ran into problems from the beginning due to the failure of “star tracker” cameras designed to determine the spacecraft’s orientation and therefore properly control its engines. Budget constraints interrupted the project, and although the command center was able to resolve some problems, the situation became more difficult on April 11, the day of the landing.

On the way to the moon, the spacecraft was traveling at high speed and had to slow down significantly to make a soft landing. Unfortunately the gyroscope failed during braking and locked the main engine. At 150 metres, Beresheet was still traveling at 500 km/h, too fast to be stopped in time.

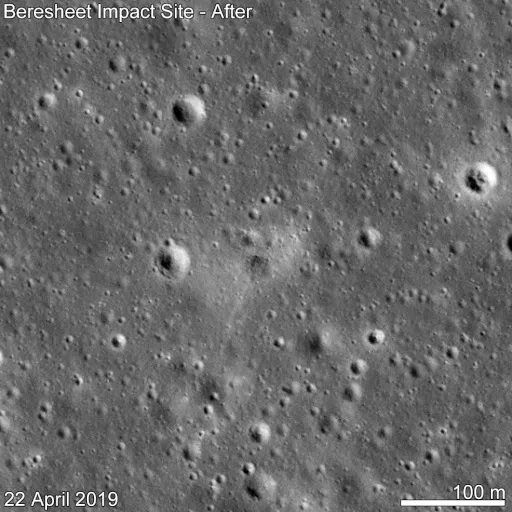

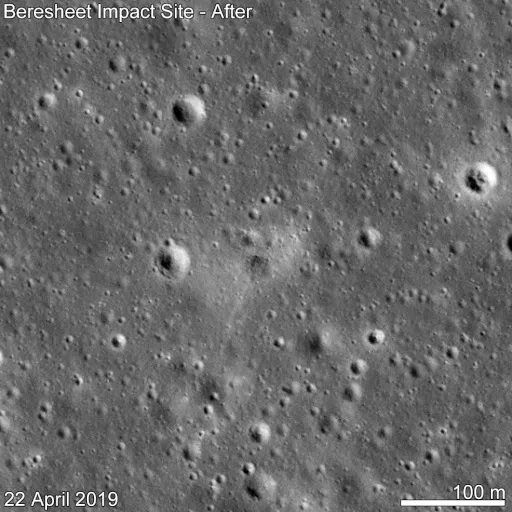

The impact was powerful; The probe broke into pieces and its debris was scattered over a distance of about a hundred metres. We know this because the crash site was photographed by NASA’s LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) satellite on April 22.

![]()

Beresheet crash site / Photo: NASA

Animals that can withstand (almost) anything

What happened to tardigrades traveling with probes? Could they be “contaminated” on the Aya, given their incredible ability to survive situations that would kill nearly any other animal? Worse still, could they reproduce and colonize it?

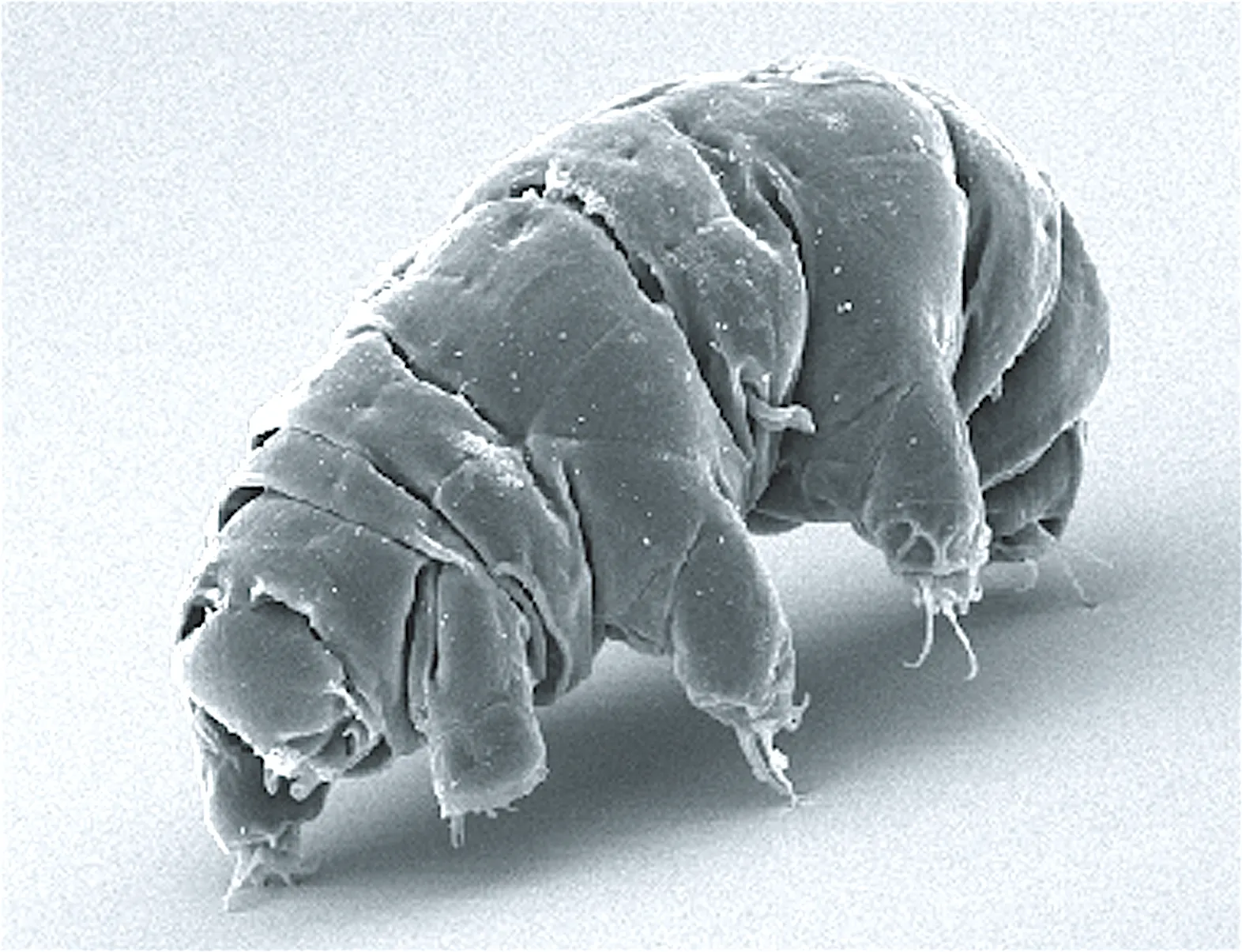

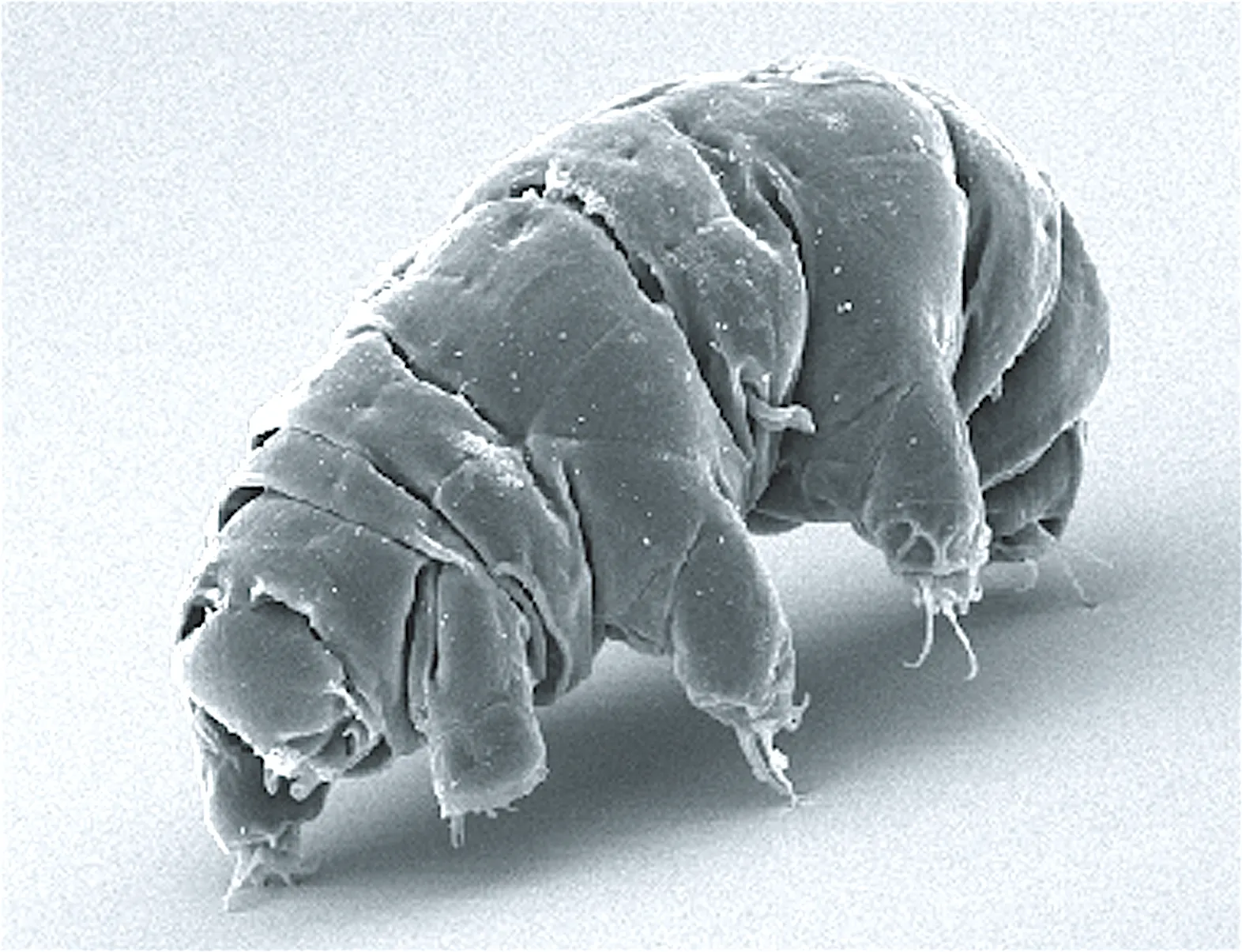

Tardigrades are microscopic animals less than a millimeter long. They all have neurons, a mouth that opens at the end of a retractable proboscis, a gut containing microbiota, four pairs of jointless legs ending in claws, and most have two eyes. Despite their small size, they share a common ancestor with arthropods such as insects and spiders.

![]()

Tychohody / Photo Wikipedia

To be active, to feed on microalgae such as chlorella, and to move, grow and reproduce, tardigrades need to be surrounded by a layer of water. They reproduce sexually or asexually through parthenogenesis (from an unfertilized egg) or even hermaphroditism, in which an individual (having both male and female gametes) self-fertilizes. After hatching, the tardigrade’s active lifespan lasts 3 to 30 months. A total of 1,265 species have been described, including two fossils.

Tardigrades are known for their resilience to conditions not found on Earth or the Moon. They can stop their metabolism, losing up to 95% of the water in the body. Some species synthesize the sugar trehalose, which acts as antifreeze, while others synthesize proteins thought to link cellular components into an amorphous “glassy” network that provides stability and protection to each cell.

During dehydration, the tardigrade’s body can shrink to half its normal size. The legs disappear, only the claws remain visible. This condition, known as cryptobiosis, continues until active living conditions become suitable again.

But not everyone can survive…

Depending on the tardigrade species, individuals need more or less time to dehydrate, and not all specimens of the same species manage to return to active life. Dehydrated adults survive for a few minutes at temperatures of -272°C or 150°C and for long periods at high doses of gamma radiation of 1000 or 4400 Gray (Gy).

For comparison, a dose of 10 Gy is lethal to humans and 40-50,000 Gy sterilizes any material. However, regardless of dose, radiation kills late oocytes. At best, the protection provided by cryptobiosis is not always clear, as in the case of Milnesium tardigradum, where radiation affects both active and dehydrated animals equally.

So how about colonizing the moon?

What happened to tardigrades after they crashed into the moon? Are there any living things buried under the dust of the lunar regolith, which varies in depth from a few meters to tens of meters?

Firstly, They had to survive the collision. Laboratory studies have shown that frozen specimens of the Hypsibius dujardini species traveling at 3,000 km/h in a vacuum suffered fatal damage when they hit sand. But they survived impacts at speeds of 1,600 mph or less, and their “hard landings” on the moon, whether intentional or not, were much slower.

The surface of the Moon is not protected from solar particles and cosmic rays, especially gamma rays, but even here tardigrades can resist. In fact, professor Robert Wimmer-Schweingruber from the University of Kiel in Germany and his team showed that the doses of gamma rays hitting the lunar surface were constant, but low compared to the doses mentioned above – over 10 years of exposure. The total dose corresponding to lunar gamma radiation is approximately 1 Gy.

But then the problem of “life” on the moon arises. In addition to lack of water, tardigrades will have to endure temperatures of -170 to -190°C on a moonlit night and 100 to 120°C during the day. A lunar day or night lasts a long time, slightly less than 15 Earth days. The probe itself was not designed to withstand such extreme conditions and would have stopped working after a few Earth days even if it had not crashed.

Unfortunately, tardigrades cannot overcome the lack of liquid water, oxygen and microalgae; They can never recover, let alone reproduce.I. Therefore, it is impossible for them to establish a colony on the Moon..

However, there are inactive samples on lunar soil, and their existence raises ethical questions. At best, at a time when space exploration is gaining momentum in every direction, contamination of other planets could mean we lose the opportunity to discover extraterrestrial life.