Vienna has found the “Holy Grail” of the residential rental market. Or at least comparisons sometimes show that tenants in the Austrian capital pay much lower prices for their homes than in other European metropolises, even in countries where wages are lower.

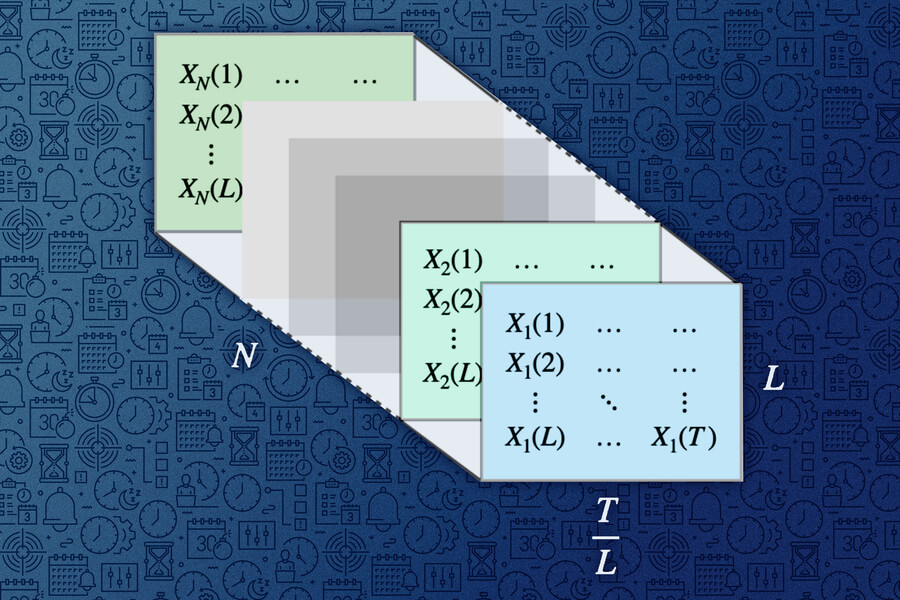

And to show a button. Consultancy firm Deloitte’s report on property markets shows that the average monthly rent in 2023 is 9.1 Euro/m2, compared to 32.8 Euro/m2 in Dublin, 28.5 in Paris, 25.8 in Amsterdam or Barcelona. It also reveals that it is well below 25.7 Euro/m2. 21.5 from Madrid. Eurostat shows that Austrian workers earn significantly more than those in Spain.

The recipe he uses to achieve this already has its own name: “The Viennese model.”

What do the numbers say? Vienna has managed to control housing rental prices, preventing their values from soaring to the privileged levels reached in other European capitals. Average prices have become more expensive here since 2021, but remain well below other major European metropolises. This is also reflected in the balance sheet published by Deloitte in 2023, in which more than fifty European cities were analyzed.

Among these, the Austrian capital is at the bottom with 9.1 €/m2, a value similar to that of Klaipéda, Lithuania’s third most populous city. It has nothing to do with the 25.7 in Barcelona, the 21.5 in Madrid, the 16.3 in Berlin, the 14.4 in Prague or the 13.3 in Rome. Despite the deep difference between salaries in Portugal and Austria, even Porto reaches a much higher average (€10.4/m2).

Corporate housing. The difference in prices is linked to another major feature of the Vienna housing market: the large weight of social and municipal housing. The city of Vienna is estimated to own and manage 220,000 socially rented apartments; This equates to approximately 25% of the local housing stock. Equal Times or Guardian It is stated that when the 200,000 cooperative houses built with municipal support are added, this is equivalent to approximately 50 percent of the population from rent subsidized measures.

|

Some EU capitals

|

AVERAGE MONTHLY RENT IN 2023 (EUR/M²)

|

|

Dublin

|

32.8

|

|

Paris

|

28.5

|

|

Amsterdam

|

25.8

|

|

Madrid

|

21.5

|

|

Copenhagen

|

21.3

|

|

Berlin

|

16.3

|

|

Warsaw

|

15.2

|

|

Prague

|

14.4

|

|

Brussels

|

14

|

|

Lisbon

|

13.7

|

|

Rome

|

13.3

|

|

Vilnius

|

13

|

|

Bratislava

|

12

|

|

Ljubljana

|

11.1

|

|

Athens

|

10.2

|

|

Budapest

|

9.6

|

|

Riga

|

9.5

|

|

Vienna

|

9.1

|

|

Bucharest

|

8.1

|

|

Sofia

|

4.6

|

More information to consider. Data on council housing may differ from one source to another, but their readings overlap: they are heavily weighted. For example, in 2021 elDiario.es interviewed two Austrian researchers from the University of Vienna; Researchers put the proportion of apartments controlled by Vienna at 45%, after warning about how complex it is to accurately calculate the percentage of apartments owned by the city. %. “We also include city-owned homes and homes from limited-benefit housing associations,” they add.

“The good international reputation of the ‘Vienna model’ has its origins in the socialist housing program carried out in the ‘Red Vienna’ of the 1920s. The program continued the city’s century-old tradition of social democratic governance and is today a professor at Social Europe, architect and urban planner Gabu “It has 420,000 non-commercial rental homes (municipal and cooperative) and the corresponding security of tenure,” Heindl notes.

Adding effort. One of the keys to the Vienna model is precisely the split of commitment between management and the involvement of developers with a very specific profile; these are developers who allow the city to directly control tens of thousands more homes than it owns. is the direct owner.

Here’s the key: limited profit housing association, “limited profit housing association.” “Vienna adopted this approach in the 1980s, when it decided to collaborate with the private sector to build affordable housing rather than develop and own more public housing,” the PD&R Office recalls.

Can you move to Spain? The data from Austria, and especially from Vienna, are far from those obtained with social housing in Spain. The public real estate stock represents 25% in the whole of Austria. Pompeu Fabra University recently analyzed data from Spain and concluded that only 2.5% of the housing stock has a social character; This rate is well below the European average of 9.3%, or the 20% that moves countries. He thinks it’s “more advanced”. OECD data does not leave Spain in a very good position either; The Netherlands stays away from Austria, Denmark or the United Kingdom.

Social housing but no ghettos. One of the keys to the Vienna model is that it does not just inject social housing into the market. It does this in such a way that it tries to prevent the formation of “pockets of poverty” by distributing such housing throughout the city, including in tourist areas. “One of the key concepts in understanding Vienna’s approach to housing is social sustainability,” he says Guardian Architecture critic Mail Novotny: “To prevent the emergence of ghettos and costly social conflicts, the city is trying to bring together people of different origins and different incomes. Social housing is not just for poor people.”

To who? That’s the key, as Novotny points out: social housing policy in the Austrian capital reaches a wide and diverse range of people. Cases with names and prices can be read in many reports devoted to the Vienna model by the world media: a university student paying 596 euros a month for a two-bedroom apartment of 54 m2 10 minutes from the central station, 360 euro in a house of 95 m2 in the 15th district A retiree paying euros or a teacher living in the capital for 450 euros in rent. It has nothing to do with the prices charged in Madrid or Barcelona.

“We want to say that everyone, from the taxi driver to the university professor, can live in council housing. This approach ensures social diversity and helps develop community spirit,” Markus Leitgeb, a spokesman for a social real estate organisation, tells Equal Times. As a result, he says, a Viennese’s postcode is “not an indicator of their income.”

The Legacy of “Red Vienna”“The city’s own housing model and a large apartment park are the result of a policy dating back a century to the ‘Red Vienna’ period after the First War. The city council launched an ambitious social housing programme. Since then the initiative has had its own history and It had its ups and downs with political changes, but it also left its mark on the housing park in the 1940s and 50s, and in 2015 the city council decided to activate the construction of municipal housing.

Effective, not perfect. The Vienna approach has allowed the capital to benefit from much cheaper rents than other European metropolises, but that does not mean it is without its flaws, as housing policy experts Justin Kadi and Sarah Kuming admit to elDiario.es. Evictions are happening in the city, despite the system designed to prevent them, prices are getting expensive, and one of the challenges of European urban planning cannot be prevented: gentrification.

In the mid-90s, an amendment was implemented in the Rent Law, which allowed not all private sector leases to be indefinite and increased temporaryity. At least in 2021, 66% of new private contracts were of this type for three, five or 10 years.

Justin Kadi, who also identified the flaws in the municipal park, says, “Over time, the system has become less rigid. It has become more friendly for landlords. It used to be very difficult to raise the rent, now it is easier,” he concludes: “Accessibility is a problem.” There is very little fluctuation in the public sector, “The contracts are indefinite, you can leave them to your children, not many can leave or enter.”

Image | Jacek Dylag (Unsplash)

in Xataka | There are thousands of empty houses in Brussels. So he will start confiscating them and renting them at a social price.