Every civilization has its own beliefs and stories. Of course, right now, a long-awaited moment is being lived with passion and excitement in the Brazilian town of Tupinamba. After more than three centuries, the town is counting down the hours for the return of one of its most sacred artifacts, the blanket.

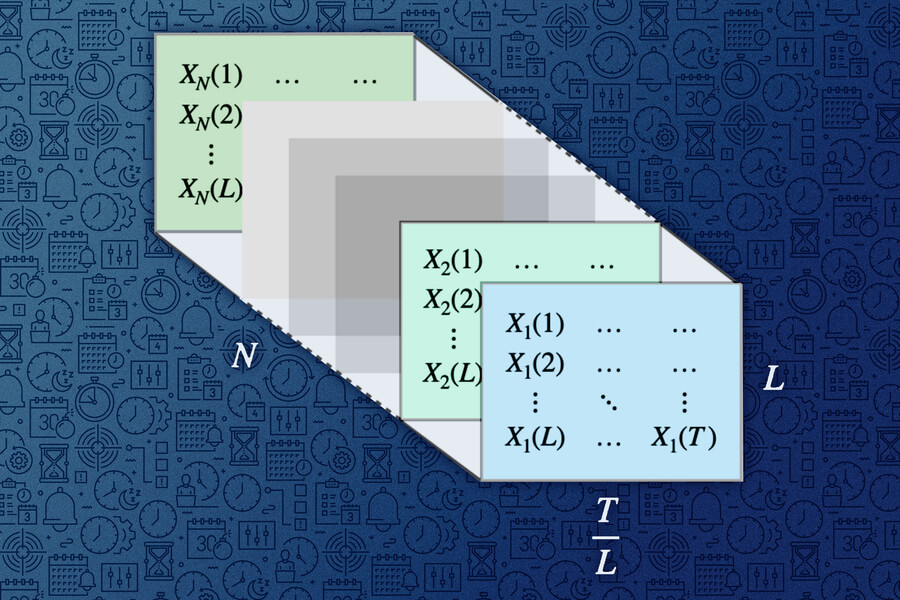

Story. The blanket (or cloak/mantle) of the Tupinamba, an indigenous people of Brazil, is a ceremonial garment made of scarlet macaw feathers, measuring just under 1.8 metres in height and containing 4,000 red feathers of the scarlet ibis. It was an important element as it carried ritual and symbolic meaning related to social hierarchies and power within the tribe, and was often used as ceremonial dress by coastal indigenous peoples.

However, the artifact was taken from the Tupinamba people during a Portuguese colonial expedition to Brazil. In fact, the Danes seized many indigenous objects through plunder and trade during their exploration of the New World, and the cloak is one of the most notable for its beauty and rarity.

Work in Europe. After the theft, the blanket was taken to the old continent as part of the collection of Frederick III in 1689, but later passed through the collections of various royal museums in Denmark, the last owner of which was the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, one of the few surviving tupinamba cloaks.

Although it also symbolizes the exploitation and plunder of indigenous cultural heritage over time, let’s consider its preservation as a testament to colonial interactions and cultural exchanges between Europe and America. It is therefore an object of study due to its intricate design and its connection to the lost traditions of the Tupinamba.

Return This is how we get to the news of these days. After more than 300 years of “exile”, the work is returning to its origins. Following Denmark’s announcement to return the tribe’s prestigious treasure (it sent it last July), the blanket was officially presented in Rio de Janeiro, in a ceremony attended by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Long wait. There, a group of 200 Tupinambá people camped outside the building, drums and all the honors waiting to see the precious shroud and reconnect with their ancient traditions. In fact, the media reported cases like that of Yakuy Tupinambá, who traveled more than 1,200 kilometers by bus from the municipality of Olivenca in the east of the country to see the shroud. I felt sadness and joy. A mixture of birth and death. When our ancestors said this [los europeos] “They took it from us, our people were left without direction.”

Tupinambá leaders say this is not just about returning artifacts to their lands, but also about recognizing indigenous peoples, their lands and their rights. In this context, President Lula said: “I am against the temporary limitation of indigenous land claims. I am in favor of the rights of indigenous peoples to their lands and cultures, as established by the Constitution.”

The importance of the work. As Amy Buono, associate professor of art history at Chapman University, explained to The Guardian, “these cloaks likely functioned as supernatural skins, transferring the life force from one living organism to another.” Tupinamba blankets were one of the most sought-after objects at the beginning of the 16th century. Many were worn by courtiers during a procession at the Duke of Württemberg’s palace in Stuttgart in 1599.

Regarding their return, the struggle for the Tupinambá of Olivença to return to their country began in 2000, when they were loaned for an exhibition in São Paulo. At that time, the Tupinambá were not officially recognized as an indigenous people; in fact, they were even described as extinct in history books. Finally, and after intense pressure, they were recognized in 2001. Eight years later, the first step was taken towards the demarcation of their own territory: an area of 47,000 hectares covering three municipalities in Bahia.

Now they finally have one of their own layers.

Image | National Museum

On Xataka | The first thing an Amazon tribe did after getting online was get addicted to porn. Or at least that’s what we want to believe

In Xataka | 100 years ago, a Galician explorer declared himself king of the Jíbaros: Alfonso I of the Amazon