One of these recurring “abnormalities” that we share among all humans was formulated a long time ago. “For whatever reason” refers to our innate ability to choose, seek, interpret, and remember information that confirms our beliefs or hypotheses. This was called confirmation bias, but there was a gap that could not be fully filled by this idea.

I’m right, the other one looks stupid. The situation is familiar and recognizable. We have all had an argument at the table with a family member or even strangers on the internet at some point, feeling like we are up against a wall, feeling like we are absolutely right even if we don’t have all the information/facts. And if the conversation concerns politics and current events, such as the situation in Palestine, the dialectic may end on a more heated note.

People tend to assume that we have all the information we need to make a decision or support our position, even if we don’t, according to research published in PLoS ONE by Ohio State University, Stanford, and Johns Hopkins. This phenomenon has been called the “illusion of information adequacy.”

Focusing. As study co-author Angus Fletcher, a theorist and neurophysiologist at the university, explains, “on average, most people do this. Interpersonal conflicts increase, leading to increased anger, anxiety and general stress.” With these issues in mind, his team began to study and analyze such misunderstandings and see if it was possible to alleviate them if possible.

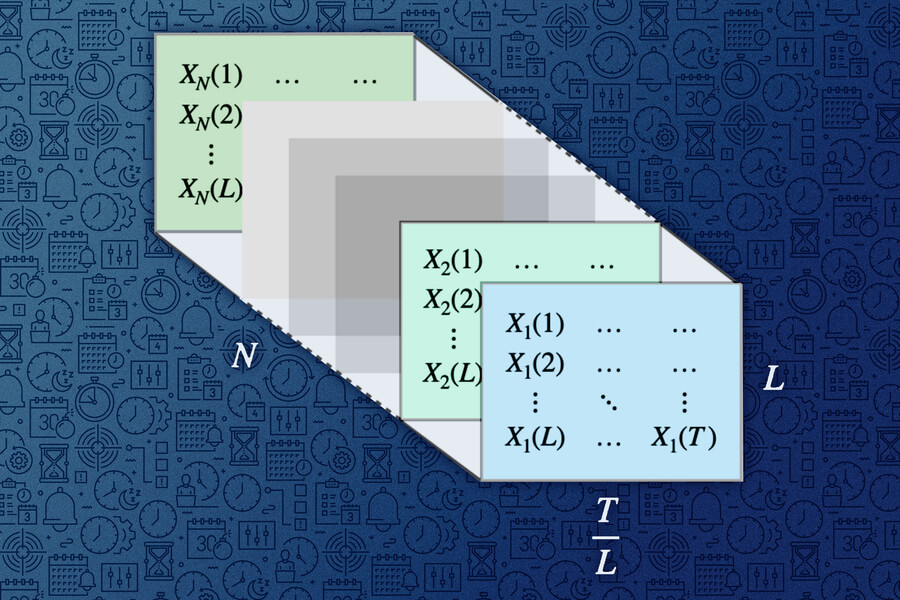

Study. In this way, the team from Ohio State University, Stanford University and Johns Hopkins University surveyed 1,261 Americans online. All participants read an article about a fictitious school that did not have enough water.

Group 1 read an article giving reasons why the school should merge with another school with better water. Group 2 read an article that simply stated reasons why schools would remain separate and hoped to find other solutions to the problem. Group 3 was the control group, which read all the arguments for merging and remaining separate schools.

Results. The researchers found that majorities in both groups who read only arguments for or against the merger believed they had enough information to make a good decision about what to do. In this case, the majority said they would follow the advice in the article they read. Those who read “pro-merger” were significantly more likely to recommend that schools merge, while “pro-separation” respondents were significantly more likely to recommend that schools remain separate.

Meanwhile, about 55% of the control group suggested merging schools. Additionally, participants with half the information said they thought most other people would make the same decision as them.

The illusion of competence. That’s what they call this bias where people believe we’re right, even if we don’t have all the information. According to Fletcher, “The less our brain knows, the more confident it is that it knows everything it needs to know. “This makes us prone to thinking we have all the important facts about a decision, and to jumping to conclusions and making definitive decisions when we don’t have the necessary information.”

Change of mind. Ultimately, what surprised the researchers most was that after everyone received the other half of the argument, their views changed so that they were the same as the control group, which included both data from the beginning.

Seeing how easily participants changed their minds, the team believes the study’s findings could be useful in everyday disagreements both large and small. According to Fletcher, “If you give people some matching data, most will say ‘that sounds pretty good’ and be content with that.”

It affects the moment. The real caveat when the indicator is at work is that the people in the study may have recently changed their minds about the ideas they formed. In other words, these were not deeply rooted ideas. In fact, a second study by this research group focusing on capital punishment was canceled.

However, is there a way to combat this bias? According to the team, one of the best ways to deal with the illusion of knowledge adequacy when you disagree with someone is to take a moment and ask ourselves: “Is there something I’m missing that would help me see and better understand their point of view?” What is your position?

You might be asking for too much, especially when you’re so sure you’re “right.”

Image | Dall-E 3/Xataka

in Xataka | The science of changing our minds: Why is it so difficult for us to admit we’re psychologically wrong?

in Xataka | There’s a reason you never start going to the gym. This is called hyperbolic discounting, and it’s happened to all of us.