“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” wrote Margaret Wolfe Hungerford in 1878, arguing that what one finds beautiful the other does not. Based on this, we now know that facial preferences vary among individuals. However, it is important to note that they are strongly shaped by culture and may even have universal components. Does the same thing happen with scents? Similarly, the perception of pleasure or odor value, which is the main dimension by which odors are classified, is said to differ between cultures.

It is not known to what extent sensory perception, especially the pleasure of smell, is based on universal principles in olfaction. But now we have a clue: We know the world’s favorite scent is vanilla.

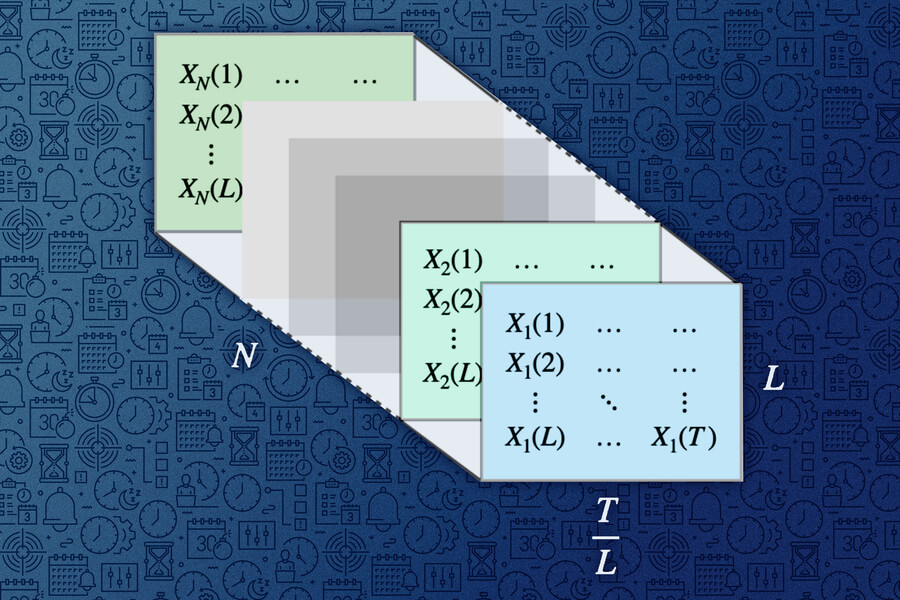

Study. conducted by the University of Oxford and the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and Current Biology set out to test the hypothesis that if odor is shaped by culture, the results must be very different. For this, they took 10 fragrances that spread throughout the world of fragrances and presented them to 235 people from nine different cultures. The study shows that there is a lot of variability in each community. On average, however, they all like the same aromas and dislike the same scents.

4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde, i.e. vanillin, the basic compound of vanilla bean, is the most pleasant molecule for participating communities. Ethyl butyrate, which is found in many fruits and gives pineapple or mango this characteristic aroma, is also highly appreciated in various parts of the planet. It is an important additive in synthesized, packaged citrus juices. Linalool, a component of many aromatic plants, or phenethyl alcohol derived from roses, cloves, orange blossom or green pine is also highly appreciated.

Why? While it is widely accepted that valence is the major perceptual axis of odor, there is widespread support for the notion that most aspects of olfactory perception are highly malleable and primarily learned, and more importantly, they have little to do with physicochemical properties. from an odorant. But by contrast, they found that cultural associations or affiliations had little effect on how much one liked a scent, and that the chemical makeup of the scent elicited likes or dislikes responses no matter where in the world they lived or what language they lived in. they talked and what are they eating

Smell taste is clearly plastic and is modulated by factors such as early exposure and context, but our data clearly show that the broader cultural context has little effect on the relative affinity of odors with one another, accounting for only 6% of the variance. In contrast, it is estimated that up to 50% of the variation in judgments of facial attractiveness may be due to culture.

The universality of fragrances. The aroma of vanilla or orange blossom is pleasing to New Yorkers, chachi of the Ecuadorian forests, or students of Ubon Ratchathani University in Thailand. At the other extreme, the smell of rotting onions or feet is unpleasant for Mexico City residents, the Mah Meri fishermen of the Malay Peninsula, or the California hunter-gatherer Seri.

“Cultures around the world categorize different scents alike regardless of where they come from, but scent preferences have a personal, if not cultural, component,” said the study’s author. He speculates that regardless of geography or lifestyle, people agree on which scents are more pleasant than others, because they may have historically been linked to a higher chance of survival. For example, our sense may trigger disdain for a particular scent as our ancestors associated it with a poisonous plant.

Bad smell also seems universal. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the molecule worst ranked by participants, whether Malaysian, Mexican, or Ecuadorian, was isovaleric acid, found in both human sweat and solid animal and vegetable oils. The smell of some French or northern Spanish cheeses. Also fragrant to many is diethyl disulfide, which comes from overripe onions or rotten potatoes. A third malodorous compound is octanoic or caprylic acid, which is naturally found in palm or coconut oils and the fat of mammalian milk.

the science of smell. Science is not as developed on smell as other senses. For example, by seeing the wavelength of light, you can guess what color it is. The frequency of the sound wave with the ear allows us to know what the sound is. However, knowing the chemical structure of a molecule does not predict well how it will smell. In addition to the thousands of possible combinations of a compound (based on atomic structure, molecular weight, concentration), the perception of odors relies on a complex that begins in the olfactory cilia of the neurons of the nasal mucosa and ends in the nasal mucosa. in the environment of each, in the aromas that have accompanied him since childhood.

In fact, mistakenly, for the majority of scientists, good or bad odor depended primarily on culture. Until now.