For decades, pediatricians have used growth charts as reference tools to chart and measure a child’s height and weight from birth to adulthood. The results often help doctors detect conditions such as obesity or poor growth. Since the dawn of medicine, there has been no gold standard for measuring the brain, which has been the cornerstone of medical care for over 200 years. Until now.

Scientists are already studying the disordered brain structure. And the charts confirm that size naturally decreases with age.

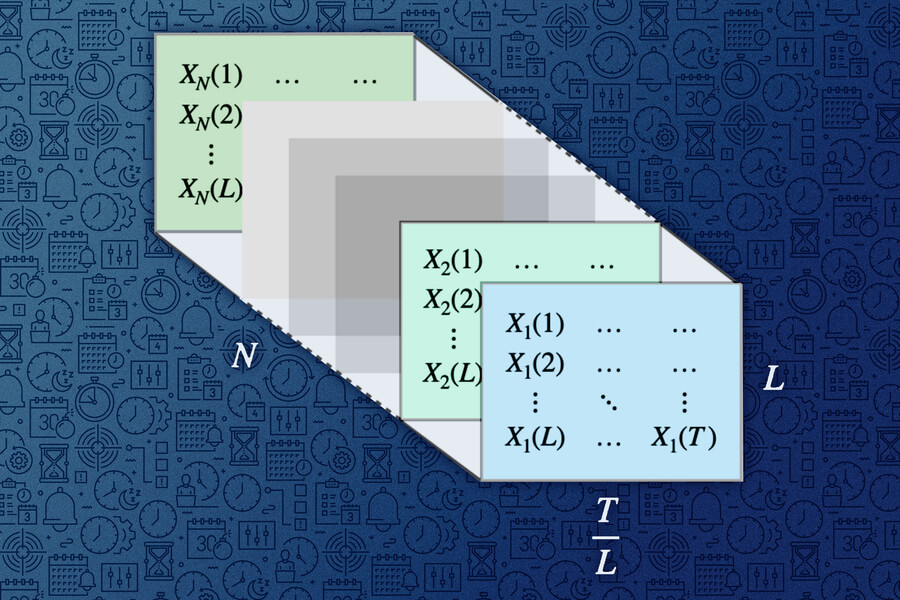

Investigation. The Brain Chart study, conducted by the University of Cambridge and published in the journal Nature, is the first to identify milestones that could potentially be used to assess whether brains are “aging healthily”. The researchers collected data from 123,984 brain MRIs of 101,457 people ranging from a three-month-old fetus to a 100-year-old person.

The study shows how the brain rapidly expands by 70% in the first years of life, from one-third of pregnancy to three years, and gradually shrinks as we age.

standard way. The volume of gray matter (or brain cells) increases rapidly in the womb and peaks before the age of six. The amount of white matter, or “brain connections,” that affects learning and brain function also increases rapidly from mid-pregnancy, but peaks before 29.

Gray matter in the lower cortex, which controls body functions and basic behavior, peaks during adolescence at 14½ years of age, while overall white matter volume decline begins to accelerate after 14 1/2.50 years of age. This helps determine if people are on a standard track.

Changes in gray and white matter volume in the brain.

Data on ventricular volume (the amount of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain) particularly surprised the authors. Scientists knew that this volume increases with age because it is often associated with brain atrophy, but they were surprised at how quickly it tends to grow in late adulthood.

differences between individuals. The data also includes large numbers of people with different clinical diagnoses. This variability makes it possible to explore differences between groups of people, as we can now see how an individual compares to others of the same age and gender. Not surprisingly, people with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, for example, tended to have low scores in gray and white matter volume, the most abundant types of brain tissue.

Data collection issues. Despite the size of the dataset, the researchers acknowledge that their study suffers from a problem unique to neuroimaging studies: a remarkable lack of diversity. The brain scans they collected come primarily from North America and Europe and disproportionately reflect populations of white, college-age, urban and wealthy. This limits the generalizability of the findings.

Billions of people worldwide do not have access to MRI machines, making it difficult to obtain a variety of neuroimaging data. But the authors did not stop experimenting. They have launched a website where they plan to update their growth charts in real time as they receive more brain scans.

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/L2T2MAX44RBNJKWNXWD6AIMELI.jpg)