An international team of researchers has found evidence of skull modification by the Hirota community on the island of Tanegashima in southern Japan from the Late Yayoi period to the Kofun period (3rd to 7th century AD). Researchers from Kyushu University and the University of Montana have published new insights into the ancient practice of intentional skull modification. Observed in various ancient civilizations around the world, this phenomenon was also found among the Hirota people.

According to a recently published report PLOS ONE These inhabitants of Tanegashima, a southern Japanese island, practiced skull modification between the 3rd and 7th centuries AD. Interestingly, the study shows no significant gender differences, suggesting that both men and women participate in this practice.

Skull modification is a form of body modification in which a person’s head is compressed or attached, usually at an early age, to permanently deform the skull. The practice predates written history, and researchers theorize that it was used to mark group membership or indicate social status.

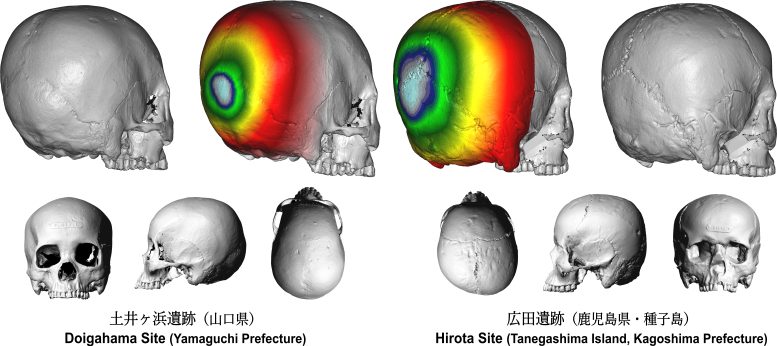

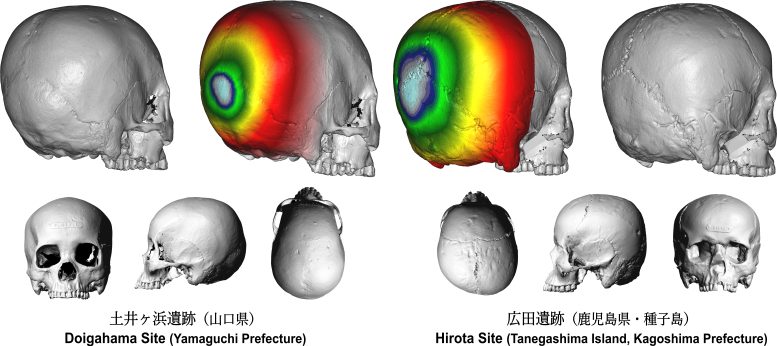

3D images of skulls extracted from the Hirota and Doigahama sites, which the researchers used to compare skull morphology between the two groups. Note that the skull in the Hirota region (right) has a more flattened occiput compared to the skulls in the Doigahama region (left), indicating deliberate skull modification. Credit: Seguchi Lab/Kyushu University

“A site long associated with skull deformation in Japan is the Hirota site on the Japanese island of Tanegashima in Kagoshima Prefecture. It is a major burial ground for the Hirota people who lived there from the end of the Yayoi period around the 3rd century AD to the Kofun period between the 5th and 7th centuries AD. .’ Noriko Seguchi of the Faculty of Social and Cultural Studies at Kyushu University, who led the research, explains.

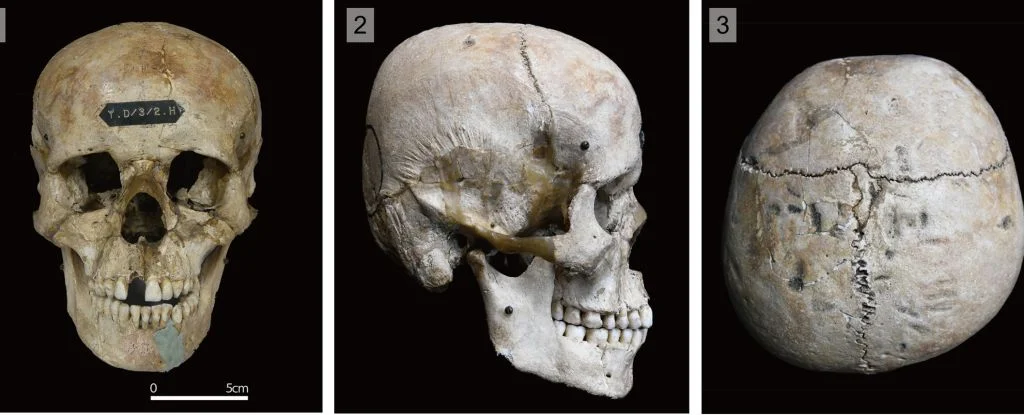

“This place was excavated from 1957 to 1959 and again from 2005 to 2006. After initial excavations, we found remains with skull deformities characterized by a short head and a flattened posterior side of the skull, particularly the occipital bone and the back of the parietal bone. . bones”. However, while the site offered an ideal opportunity to study the phenomenon, it remained unclear whether these skull changes were intentional or the unintentional result of other habits.

To conduct the study, the research team used a hybrid approach, using 2D images to analyze the skulls’ outlines and 3D scans of their surfaces. The team also compared skull data from other archaeological sites in Japan, such as the Doigahama Yayoi people of western Yamaguta and the Jomon people of Kyushu Island, who were hunter-gatherers and ancestors of the Yayoi people. The team collected all this data, along with a visual assessment of skull morphology, and statically analyzed the contours and shapes between the skulls.

A photograph of Hirota’s home in present-day Tanegashima, Japan. Each sign indicates where the burials were found, with notes on their gender and approximate age ranges. Credit: Kyushu University Museum

“Our results revealed significant cranial morphology and significant statistical variability between Hirota individuals and Kyushu Jomon and Doigahama Yayoi specimens,” Seguchi continues. “The presence of a flattened posterior part of the skull, characterized by changes in the occipital bone, with depressions in the parts of the skull that connect the bones, particularly the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, strongly suggests an intentional modification of the skull.”

The reasons for this practice remain unclear, but researchers think the Hirota people deformed their skulls to preserve their group identity and potentially facilitate long-distance shellfish trade, supported by archaeological evidence found in the area.

“Our findings add significantly to our understanding of the practice of deliberate skull modification in ancient populations,” Seguchi said. “We hope that further research in the region will offer more insight into the social and cultural significance of this practice in East Asia and around the world.” Source