When green is bad

Tiny microbes, including algae, use green chlorophyll for photosynthesis. So the more their number, the greener their habitat. But as attractive as a green world may seem, the spike in phytoplankton concentrations is likely to have numerous side effects for ocean ecosystems.

We are already witnessing the severe short-term effects of heat-induced increases in phytoplankton. A sudden population explosion deprives the environment of oxygen and creates hypoxic dead zones from which all animals cannot escape.

But there are longer-term consequences that we have yet to learn.

One of the open questions about these long-term changes is how much data will be enough to detect them: thirty years of observation will be required.

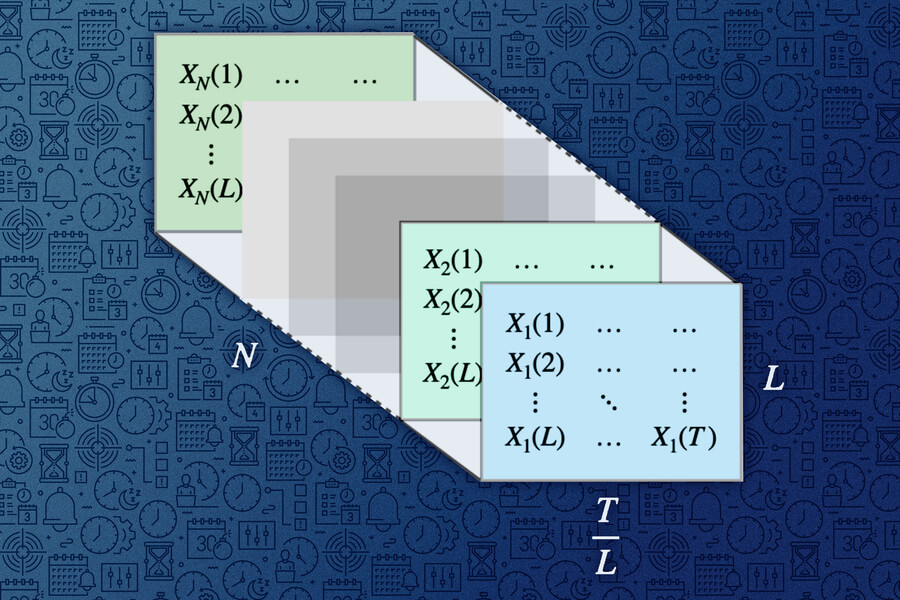

Ocean surface color change map where darkness means more pronounced effect / Photo by Cael/Nature

In this image, a research team has shown that nearly 20 years of data from the MODIS-Aqua satellite is enough to help us observe, understand and respond to climate change more quickly.

This rapid response is possible thanks to the remote sensing of the reflection, which allows the color of the ocean to be displayed based on the reflected light. Processing these images is in some ways simpler than trying to measure phytoplankton populations using other methods, such as estimating chlorophyll content.

The researchers acknowledge that this does not mean that phytoplankton is the only reason the ocean is greener. However, their analysis is closely related to an advanced model that predicts how ocean ecosystems might respond to climate change.

Remote sensing reflectivity, and thus surface ocean ecology, has changed dramatically over much of the ocean over the past 20 years.

– researchers write in their published paper.

The greening of the ocean was especially noticeable near the equator.

Because phytoplankton absorb carbon dioxide, their increased abundance can be seen as a valuable carbon sink, making this relationship more complex than it first appears.

But because phytoplankton are the backbone of the marine food chain and can change many parameters of their environment, including temperature, nutrient availability and light levels in the water, increasing their numbers can also cause significant changes in resources such as protected areas. fishery So it will probably do more harm than good.

The study doesn’t delve too deeply into the results, but whatever this ocean greening means, it seems like it’s already happening — a decade earlier than expected. Overall, these results suggest that the effects of climate change are already being felt in surface marine microbial ecosystems, but not yet detected by humans.