Anyone who saw Professor Nathaniel Kleitman and his assistant, graduate student Bruce Richardson, descending into Mammoth Cave on June 4, 1938, would think they were part of a geological expedition or the advance team of a team of archaeologists. Ancient sites. Normal. Jackets and hoodies up to their eyebrows, packed with backpacks, flashlights and books, the odd couple looked like a cross between Indiana Jones and Charles Darwin during their good years of exploration.

Which Kleitman and Richardson They were searching deep within Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, away from sunlight, the hum of traffic, and other stimuli that would remind them of the frenetic pace of civilization; This was something very different: sleep. His purpose was to sleep. Although of course you follow certain rules.

All to better understand sleep cycles and answer a question that seems as simple as it is complex: Do we have to stick to 24-hour days? Do people have a cycle based on this program? Could we adjust our circadian rhythms if we wanted to?

Goal: Isolate yourself from the world and the days

Kleitman was determined to get answers. And he also wanted to do it his own way, from a first-person perspective, by experimenting with his own body or, if necessary, with his own nights of sleep. To this end, he and Richardson decided to conduct an experiment that, even today, 85 years later, is ranked among the “TOP 10” of history’s most misleading scientific tests.

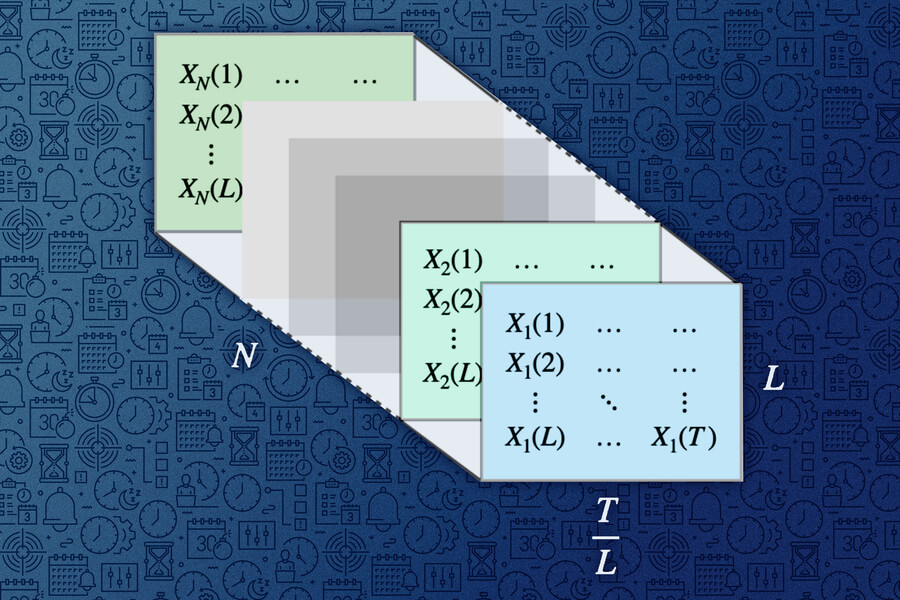

For just over a month (32 days to be exact), both scientists voluntarily remained holed up in the Kentucky cave to adapt to climate change. a 28 hour day. Their goal was relatively simple: instead of “living” the following weeks with seven 24-hour days, Professor Kleitman and his assistant tried to adapt to another, slightly different format: six days, special days only, four hours more than the traditional ones.

The experiment was strange. Instructions that are necessary, or at least that Professor Kleitman considers more helpful. The researchers wanted to adapt to 28-hour days by taking advantage of “uniform temperature and lighting conditions” and the “peace of the cave.”

So they chose Mammoth, which is more than 42.5 meters deep, has no natural light, shows whether the moon is shining, and has a constant temperature of 12.2°C. It might not be the most comfortable lab in the world, but the scientists made up for it with artificial light from flashlights, a table, and a bunk bed to protect them from cave rats. As for their routine, they devoted ten hours to work, nine hours to recreation, and the same amount to sleep. Bedtimes also changed throughout the study.

Where did the food come from? a nearby hotel to Mammoth Cave after Kleitman gave those in charge some very precise instructions based on the “surface time” of deliveries and adapted to their own sleep-wake cycles. The first meal was served from 1pm to 5pm or 9am depending on the day of the experiment. The only people Kleitman and Richardson had contact with from the outside world during these 32 days were food delivery personnel and a courier responsible for distributing and collecting letters.

“The goal was to see how sleep could be induced, especially in the absence of normal environmental cues such as light and temperature,” sleep researcher Jerome Siegel of the University of California, Berkeley, explained to the journal in 2016. the scientist. One of its aims was to study the body’s ability to adapt to a cycle outside of the normal 24-hour cycle; For this it was necessary, among other things, to control how the body temperature cycle develops.

different reactions

Interestingly, despite the self-imposed 28-hour rhythm, scientists have confirmed an endogenously generated 24-hour cycle of body heat. They found that even in the absence of external signals, bodies maintain a 24-hour temperature cycle that appears to be linked to their own feelings of sleepiness.

Not only that. The reaction of both Professor Kleitman and his assistant, Richardson, who had a considerable age gap, was intriguing. At first, for the almost 43-year-old Kleitman, the change seemed like a world of big deal to him. Despite the new schedule, he continued to feel tired around ten at night and remained awake eight hours later. His colleague Richardmon, who is twenty years younger, adapt better Change in pattern after a week in the cave.

Their findings did not remain a collection of measurements and an interesting experiment in the anecdotes of the history of science. In 1939, Kleitman expressed his conclusions in a book titled ‘Sleep and Waking’. New York Times– shortly after, II. During World War II, he used his data to advise soldiers and workers to follow regular shifts. Their goal: To allow their bodies to adapt to a 24-hour cycle, leading to increased efficiency in performing their tasks.

The Kentucky cave experiment may be the most intriguing of all the experiments Kleitman performed, but it is not the only one that demonstrates his scientific enthusiasm and his willingness to push his work to extremes. It must be said that everything was extreme, which he did not hesitate to apply to his flesh, as he showed in ’38.

Many years later, in 1948, Kleitman passed the Mammoth Cave test. two weeks He boarded submarines to study sailors’ sleep patterns, and in the 1950s he experimented with sleep deprivation to an almost insane extreme: He once stayed awake for 180 hours. “There comes a point where someone will confess to anything just so they can sleep,” he said. Guardian.

Unfortunately, his words did not stop there, and sleep deprivation was effectively used as a form of torture, which, for example, PIDE agents in Portugal did not hesitate to resort to during the Salazar dictatorship.

Image | US Government and Renel Wackett

in Xataka | For years we thought we needed to sleep eight hours a day. We probably sleep too much.

in Xataka | In the Middle Ages, it was common to sleep in wooden cabinets. The real question is why we stopped doing this.

*An earlier version of this article was published in May 2023.